One Hand Clapping – September 2004

— William Michaelian

Note: Each month of One Hand Clapping has been assigned its own page. Links are provided here, and again at the bottom of each journal page. To go to the beginning of Volume 2, click here.

March 2003 April 2003 May 2003 June 2003 July 2003 August 2003 September 2003

October 2003 November 2003 December 2003 January 2004 February 2004 March 2004

April 2004 May 2004 June 2004 July 2004 August 2004 September 2004

October 2004 November 2004 December 2004 January 2005 February 2005 March 2005

September 1, 2004 — The telephone just rang. It was someone I know, wanting me to do something I don’t want to do, but that I will do anyway because he needs and expects me to do it. To be more precise, he needs someone to do it, and expects me to do it, because I have done such things for him in the past. In other words, it’s my fault for not telling him to find someone else. Naturally, I didn’t let on that I don’t want to do what he wants me to do. I’m too polite and too stupid for that. And yet all I would have to do is tell him that I am no longer available to do what he wants me to do. He wouldn’t even be upset. The fact is, he doesn’t care. His only concern is getting done what he needs done. Even more ridiculous is that we aren’t friends, though we have known each other since 1988. And if we have known each other since 1988 and still aren’t friends, it isn’t likely that we will ever be friends. Not that he isn’t a nice enough guy. He’s plenty nice. We just have nothing in common, except for what he calls me about and wants me to do. I keep thinking that one of these days I will tell him — politely and with all due respect, of course — I’m through. It would simplify my existence, and only complicate his for about one minute. I even know who he would call in my place. Then life would go on. The question, then, is, why don’t I go ahead and tell him? Is it because he pays me to do what he needs and wants me to do? Possibly. And yet, the money is so little that it would hardly be missed. It isn’t a matter of survival. Do I put the money in the bank? No. It’s spent before he gives it to me. Every cent I have has already been spent. The only reason I hang onto to it is to tease my creditors. “Oh, well, then, here you go,” I tell them eventually. “If it’s really that important to you, go ahead. Take it.” If this sounds contradictory, that’s because it is. I have a very strange relationship with money. I need it desperately, but I hate it and don’t want it. At the same time, I do want it — but only because I need it. The good thing is, this gives me an understanding of money that the average business person lacks. It is this lack of understanding that allows business people to succeed, and simultaneously leads them to believe all sorts of silly things about themselves that they couldn’t possibly believe if they had no money. The funny thing about it is, these very thoughts go through my mind every time this person calls me — which, fortunately, isn’t very often. If he called me every day, I don’t know what I’d do. Sometimes I won’t hear from him for two weeks. Those are happy days, indeed.

September 2, 2004 — And then there are people I want to hear from, but who choose to remain silent for exaggerated periods of time. I write to them and get no answer. I ask them pertinent questions, or specifically address something they have said, or mention something important that’s happening on my end, and then receive silence in return. When they ask me something or tell me about their problems, I always reply, whether I have time or not, and whether or not I’m in the mood. I reply even if they don’t ask me or tell me anything, and are just writing to say hello. When someone says hello, I say hello back. I do so because it’s a natural impulse to acknowledge someone’s greeting, and because I know what it feels like when someone doesn’t acknowledge mine. Eventually, though, my anger subsides, and then I start to worry about the people I haven’t heard from. Everyone has their own set of problems, be it health, mental, or otherwise, and to some degree everyone is held hostage by the lunacy of modern life. Often, at the end of the day, it hurts to think, and it seems nearly impossible to compose a reasonable reply to someone’s urgent ramblings. I am accustomed to writing all the time, so maybe it’s easier for me. I find the act of writing, in whatever form, to be therapeutic. I get caught up in it, and soon I feel better, and less tired. What physical exercise does for the body, writing does for my withered gray matter. It creates a positive charge, and gives me the energy I need to continue on. And continue I must, because so many things remain unsolved. That I will solve them by writing I know sounds foolish. But unless I am horribly mistaken, writing is the tool I am meant to use. Writing is like a shovel. With it I dig myself deeper into trouble, and yet with that same shovel I will dig myself out — assuming the handle doesn’t break.

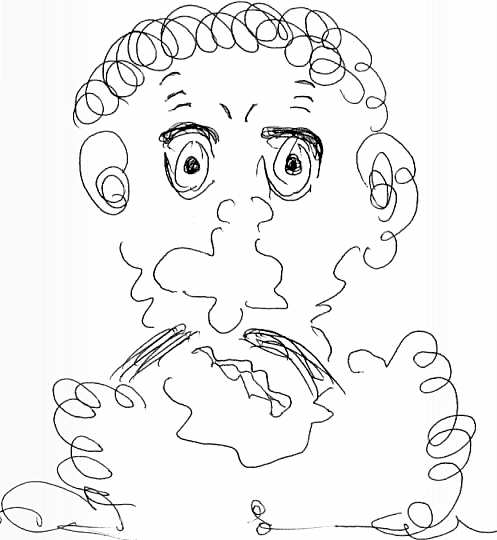

September 3, 2004 — Good news: I’ve decided to undertake several new projects. The idea came to me late yesterday afternoon. “What you need,” I said, “are new projects — not two or three, but a dozen or more.” And so I quickly wrote down the word Projects on a slip of paper. Whenever I write something on a slip of paper, that makes it official. “Oh, no,” I said, holding the paper up to the light. “You realize what this means, don’t you? It means you’re stuck. Now you have to follow through.” Undaunted, I started thinking about what projects I might undertake. Possibilities rushed in. “Pick me! Pick me!” they all yelled. “I’m the project to end all projects.” Some of them weren’t bad, so I threw them into a pile on the corner of my work table and let them argue while I considered the other rapidly accumulating projects. A scribble here, a crumple there, a sketch, a scratch, a puzzle. Hmm. Ah. No. Oh? Ah-ha! Why didn’t I think of that before? Where was I yesterday? What have I been doing with my life? What a fool I’ve been all these years! Just then, my wife walked in. “What on earth is going on in here?” she said. I looked up at her. “From now on,” I said defiantly, “things are going to be different around here. There are going to be major changes.” She sighed. “Again?” she said. “What is it this time?” She looked at the mess I was making. “I know what you’re thinking,” I said. “But don’t say it. This pile of scraps represents what’s going on in my head.” Her smile was sweet and full of understanding. At the same time, it was obvious that she felt she had proved her point. But so what? Since when has it been hard to prove I’m off my rocker? Besides, I still have my projects. I have them, and no one can take them away from me. I know the truth — and the truth is, I can’t be stopped.

September 4, 2004 — Our new neighbors have placed a gallon container of yellow chrysanthemums on each of the two decorative concrete swans near their front step. The swans have a little round platform growing out of their backs, making them look somewhat deformed. But the general scene is a cheerful one, and there is every indication that these people are nothing like the former troublemakers who tried to destroy the place. Meanwhile, the spitter across the street has taken his adorable little family on a vacation somewhere. They have been gone a week. And what a pleasure it has been to see their house sealed like a tomb, and not to have to listen to the daily spitting and yelling. The neighbors around the corner are in charge of picking up the newspaper every morning. One day they didn’t bother until evening, and usually the paper sits there half the day announcing the owner’s absence. But, in all fairness to the paper-picker-uppers, it takes time to decide which of their shiny SUVs to drive on their many important trips each day to the video store, hair parlor, and club meetings. Not that any of this is true, mind you. I don’t really know where they go, or why it takes such monstrous vehicles to haul one or two people. Maybe they do contract work for local mortuaries. You Call, We Haul. There is also another problem developing. When the spitter parked his pickup by the curb before he left, he left one of the interior lights on. It flickered bravely for three or four days, but it has finally gone out. I feel just terrible about him having to face a dead battery when he gets home. Why, he’ll be mad enough to spit.

September 5, 2004 — Good little student of literature that I am, I read one of the short stories in the stack of Harper’s magazines that recently came my way. I chose a story by a well known writer with several novels and story collections to his credit — not too difficult since the authors whose work appears in the magazine generally have an extensive track record, or have at least “studied” with important writers no one has heard of, or have attended several prestigious workshops. The story was terrible. It was hopeless. Nothing happened. Its author was playing a clever word game, depending on his vocabulary to carry the piece, which it did — right into the garbage. Quite simply, he did not care about his characters. He couldn’t, because he never got to know them, never gave them a chance to speak for themselves. There were a couple of almost-observations, and there was some almost-sex thrown in at the end, when the author apparently realized he’d better do something. He was too late. He took the money and ran. I suppose Harper’s can afford that sort of thing, but I refuse to believe that in a country this size it isn’t possible to find better stories. The reason Harper’s can’t or doesn’t bother, I would guess, is that the editors feel the same about their work as the author who took the money and ran: this will do, the bases are covered, and so on and so forth. How boring, and what a waste of ink, paper, and circulation. . . . Now, there is something else on my mind, and that is the rather dramatic dream I had last night, in which my old piano teacher, Mrs. Crawford, had risen from the dead to give a masterful performance of Chopin’s Polonaise at the top of some wide steps in a huge abandoned building. As a crowd gathered, I felt tremendously proud to see her performing on her shiny-black grand piano. She began softly with another piece of music, but soon she became inspired and switched to Chopin, hammering out the Dum-de-dum, dum-dum-Dum-dee-dee-dum with her ancient bony fingers. When she finished, the crowd erupted into applause, and she looked so happy I thought I would cry. I met her soon thereafter, surrounded by a group of admirers. I told her how beautifully she had played, and reminded her of the difficulty I’d had with the piece years earlier when it had been part of our lessons. Growing younger every second, she smiled and said, “With you, it is a gift, because the music is in you.” And then I found myself alone in the building, wondering about what she had said. I knew it was true, because she had said it. But what I didn’t know, and still don’t, is what she really meant. Was she referring to music, or writing, or was she perhaps referring to living itself? And then there was the way she had spoken: it seemed she was giving me her permission to — what? be myself? I know this: if anyone could grant such a preposterous thing, it would be her, and she would do it in just that manner, simply and graciously, without drawing attention to herself. And here is another question: why that particular piece of music? I haven’t heard or thought of it for years — which begs yet another question: what else haven’t I heard or thought of for years?

September 6, 2004 — Maybe now is the time to read some Shakespeare. The book is still sitting here, right in front of me. I read the introductory material, which was quite interesting, but then I became distracted and read three novels and a collection of stories, some poems, and a few pages of Mencken. (A writer knows he has arrived when people refer to him by his last name. With any luck, he is still alive when this happens. But if he’s dead, he still knows. This is my hope, at any rate.) But even as I say this, I doubt I actually will read Shakespeare. For one thing, he and Kafka aren’t speaking to each other. I never should have left them together on the table, since Shakespeare fills a massive tome, while Kafka is relegated to a few pages in a fusty anthology between Faulkner and Wolfe, who are a couple of windbags. For the last couple of minutes, Kafka has done nothing but blink and sigh. And I can see that Shakespeare would like nothing more than to argue and brag about his accomplishments. It’s sad, really. They’re both dead, and yet they persist in this childish behavior. And Mencken is dead, and Faulkner, and Wolfe, and almost everyone else. Am I dead? Quite possibly. I can’t say for sure that I am alive. I think I am, but everyone else thinks they’re alive too. That’s hardly encouraging, when you consider some of the other things that everyone else thinks. Maybe I’m just tired. But I’m not. I’m full of energy. I feel great. I feel rotten, too, but that’s to be expected, because feeling rotten is part of feeling great. Once, after a particularly emotional funeral, I told an Armenian priest that I liked funerals. He couldn’t understand it. I told him grief is a beautiful thing, and that it brings out the best in people. This he almost understood, but he was too caught up in the idea that sorrow is bad and happiness is good for it to soak in — as if they were two separate things, which of course they’re not, because nothing is separate. Everything is part of everything else. That’s why I felt so happy during the funeral, and so sad, and why I usually feel that way in general. Now all I need to do is to figure out what this means.

September 7, 2004 — I read two more Harper’s stories last night. One wasn’t really a story, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing as long as something is said and said well. But nothing was said. There was no point — or, if there was, the author was determined to keep it a secret. The second story wasn’t a story either, but it was a vignette, though a lifeless one that didn’t work the way its prize-winning author hoped it would. It might have if she had been specific, and not treated her characters like crash-test dummies. On the other hand, she did use several French words and phrases, and though I didn’t understand them, I felt, how do you say? sophisticated. All in all, this Harper’s story thing has become quite a challenge. It’s beginning to look like I’ll have to read several more. I might even turn it into an all-out “Quest for a Genuine Story” and read three or four years’ worth. Meanwhile, I have a stack of The Atlantic to go through. But I fear this will be like switching from McDonald’s to Burger King. Not that I mean to sound bitter. Heaven forbid. They’re only trying to run businesses, after all. What gets me is the pretending. They say they are publishing stories, or fiction, or literature, but their spread sheets are showing.

September 8, 2004 — What a shame that each war-related death in Iraq — on both sides — as well as each and every injury, doesn’t merit the same attention as Milestone U.S. Death Number 1,000. After all, wasn’t the number reached one tragic, bleeding moment at a time? And yet during a visit to Portland yesterday, “National Security Advisor” Condoleeza Rice had the nerve to say that the U.S. is winning the war, both against terrorism and in Iraq. She said it with the same smirk that she, Bush, Cheney, and Rumsfeld are unable to wipe off their faces when they utter their hideous lies. And who can blame them? Look at what they have gotten away with, and continue to get away with. Despite the illegitimacy of Bush’s presidency, it is important to remember that millions of people did vote for him. Can anything be more frightening? What are those people going to do when the 2004 election rolls around? Have they learned anything? Have they been paying attention? Have they taken note of the lies, the destruction, the lost jobs, the continued assault on the environment? Have they bothered to notice who is profiting from the war? And do they think the next 1,000 deaths will be any less painful? Because if they grant the monsters another four years, 1,000 will quickly turn into 2,000, and 2,000 will turn into 5,000. If Bush stays in office, by legitimate or fraudulent means, his first term will seem like a picnic compared to what lies ahead.

September 9, 2004 — If it were a few degrees cooler this morning, I would be able to wear my new gray sport coat. I found it yesterday, with the help of my long suffering bride, at Goodwill. We had looked for one off and on last year, but not until it was late in the season. Then, a couple of days ago, it occurred to me that we would have better luck finding one now, while it is still relatively warm. Such is my keen fashion sense. The coat fits perfectly, is made of wool, and is worth every bit of its $7.99 price tag. The funny thing about these coats — my black one is also from Goodwill — is that they are better than anything I can find in department stores — which is interesting, since that is where they originally came from. But there is something wonderful about a coat that has been worn. The stiff, careful period is over, and its true personality begins to show through. It is possible to relax in such a coat, to move freely, and to not worry about it coming in contact with the elements. The fact that it is still here proves its worth and durability, thereby giving its wearer a feeling of confidence. That’s why, when I see men wearing new sport coats and looking like strangled two-by-fours, I feel sorry for them. There is nowhere that I would be ashamed to be seen in either of my sport coats, be it a wedding, funeral, or meeting with the governor. That’s how good they look, and how confident I am in their ability to make the right impression. Now, this reminds me of the time my brother and I were in Armenia in 1982, seeing the country and visiting with our grandfather’s cousin, who has since passed on. Papken always wore a coat and tie, and he smoked cigarettes and loved to talk. One evening we were visiting a friend of his, and while he was going on and on about something or other, he forgot to flick the ash off the end of his cigarette. The ash grew and grew, until it was nearly two-thirds the length of the original cigarette. It sagged, but somehow it held together, though the cigarette was in his mouth much of the time. My brother and I watched with amusement until the ash finally broke free and landed on his sport coat. Papken didn’t notice. He went right on talking, as the chunks of ash slowly found their way through the creases and fiber to the floor. I wonder where that coat is now. Maybe Papken was buried in it, or maybe someone in Armenia is wearing it still, and absorbing its wisdom and energy.

September 10, 2004 — I woke up at about three-thirty this morning and couldn’t go back to sleep. Now it’s almost eight and I can’t wake up. I’m here at my post, but an entire army might already have passed behind me without my knowing it. Or a herd of cattle, on its way to slaughter — not that there are any similarities between the two. No. Of course not. Let us speak plainly, then. Let us not mince words. Let us say there is a light fog this morning, and that scarcely a tired, dirty maple leaf is stirring. Let us say the spitting neighbor is back, and that he just did what I enjoyed so much not hearing him do while he was gone on vacation. Let us also say that he has yet to try starting his pickup and still doesn’t know about his dead battery. Finally, let us say that I am tired of saying let us say. Summer is dying a slow, graceful death. Fall is peeking through the leaves and starting small fires along the roadside. Winter is biding her time. Spring is busy reading next year’s seed catalogs. Everywhere, the ground aches underfoot. It aches with a thousand unanswered questions and misunderstood replies. Lean messengers run from village to village with the news, but they are really looking for brides, for they are tired of running, and tired of being alone. The young women know this, and greet them as they approach. What news do you bring? Have you seen our friends? But the messengers look at them strangely. They say everyone in the village has been killed, or that they have all gone mad. They make up fantastic stories, causing the young women to tremble. If it is so, what will become of us? But they know it is a game, and they walk hand in hand with the messengers into the village. When they arrive, the elders smile, for they, too, know. They remember, and laugh, Is everyone in your village still mad? Yes, yes. Of course we are mad. We are all mad, and we have all been killed. But with your kind blessing, your daughter and I will go back and save them. It is the least we can do. The blessing is given, and then there is a great celebration. This is how we live. This is how we die. Please, go about your business. Ignore the man behind the curtain. He is the maddest villager of them all.

September 11, 2004 — In downtown Salem yesterday, I held a door open for two babbling Mexican women pushing strollers. Then, as it happened, there was another door several feet ahead, and since they reached it before I did, one of them held it open for me and said with a smile, “Now is my torn.” I thanked her and passed through, thinking how nice it would be if everyone were so friendly and willing to take torns. And earlier, when I was in a print shop on extremely important and highly confidential business — so important and confidential that even I didn’t know what it was — I found myself stranded at a busy counter with customers lined up on one side and employees lined up on the other. The customers looked like they were ordering sandwiches, while the employees seemed uncertain of their menu. And even earlier — so early, in fact, that it was the day before — upon leaving the bank, I asked the Russian who sells hot dogs on the corner how he was doing. He flashed a silver-laden smile and said, “Very good, thenk you,” just as if he had already sold a hot dog to every citizen of Salem, and I was the only one he had missed. It was inspiring to see a genuine old-style entrepreneur in action, bringing life to a street corner. What a shame there aren’t also paper boys on the sidewalk hollering the day’s headlines from beneath floppy woolen caps: President reads book! President holds map upside down! Then we’d be getting somewhere. What a time this is, really. It seems so much life has been snuffed out of people, and behavior is so regulated and predictable. Worst of all, hardly anyone gets my jokes anymore. People just look at me — and look, and look, and look. Well, I’m sorry, buddy, but if you don’t get it by now, you’re not likely to anytime in the near future, so why don’t you just go home and watch your little screen, or big screen, as the case may be. I’m sure you can find a cheap money-mad game show, or talk show, or reality show, or something else you’ve seen 10,000 times. When you’re through, come back. I’ll still be here. Maybe then we can talk, unless you’re too busy playing games on your cell phone, or whatever they call them these days. Hello? Hello? No, I can’t talk now, I’m using the shaving attachment on my phone. I’m networking. I’m conferencing. Oh, really? Good for you. I’m baking a damn cake.

September 12, 2004 — Phlegm update: Finally, after two weeks, the neighbor tried to start his pickup. He opened his garage door yesterday morning and coughed and spat his way to the street, unlocked the pickup, and sat down behind the wheel. Click-click-click. Nothing. He got out of the pickup and coughed again, and then, splat. The coughing, spitting, and splatting when on for half an hour while he tried to jump-start the battery with his van. Click-click-click. It might have helped if he had started the van and left it running, and given the battery a chance to charge, but he didn’t. He went back inside, then returned a couple of minutes later, spitting. He called someone on his cell phone, and actually spat during the conversation. When he hung up, he realized he was standing in a river of phlegm, and that the drain in the gutter had backed up. The phlegm had crept over his neighbor’s sidewalk next door. Birds were falling dead out of the trees. Sirens wailed in the distance. He was trapped. Luckily, our house is across the street and on higher ground. As our moat filled with phlegm, I raised the drawbridge. Then I fired several cannons, killing the neighbor and destroying his house. A giant crater formed, swallowing them, it, everything. This morning, the street is quiet. I am at peace.

September 13, 2004 — Now our iris worker has a nice fat bank account and is back in school. He still has a couple of Saturdays to work on the farm, then the season will be officially over. Meanwhile, the farm owners will enter a new cycle of activity, one that moves along at a slower, saner, more human pace. Back in my farming days, this didn’t happen until October. Then the Fresno Fair opened and I’d sneak off and spend a day at the horse races, which was an ideal place to study human behavior, including my own. Now in his senior year of high school, and having satisfied almost all of his so-called educational requirements, our son is attending school in the mornings only. One of his classes will focus on Shakespeare, so it will be interesting to hear his impressions. In the afternoon he will be free to “study” and play his guitar — in fact, he claims a new one is on the horizon, now that he has money. He’s still talking about buying a twelve-string acoustic, which I think is a fine idea, especially since he is the one who will be paying for it. The house is full of music these days, as he and his older brother have continued their guitar explorations. Vahan has three amps now, two guitars, and another on the way that he says is “just a junk guitar” that he plans to “experiment on.” Judging by the progress the boys have made — boys? Vahan is twenty-three — I’m one hundred percent behind their activities. Vahan, who is quite a wizard in computer matters and is actually paid for his knowledge and ability, has said many times that the last thing he wants to be is a geek who knows nothing beyond the computer realm. Between his musical pursuits and extensive reading, I would say there is no danger of that. There is also no danger of me becoming a computer geek, or even a productive citizen — at least in ordinary terms. For the truth is, I am quite productive, even though most people think I do nothing. I find this extremely amusing, and purposely encourage their misguided perceptions. It certainly beats explaining why I mumble to myself and hit my head against the wall.

September 14, 2004 — Propaganda, anyone? How about this front page headline in today’s Oregonian: “U.S. risks losing Iraqis’ support.” That’s a clever one, all right. It’s clever because it assumes the U.S. once had the Iraqis’ support, and also because it assumes the U.S. still does — despite the occupation, despite the U.S. takeover of the Iraqi economy, despite the ongoing death and destruction of the Iraqis’ families and homes. This kind of propaganda goes on day in and day out. “We” are liberators. “They” are insurgents and terrorists. And yet, who is on whose soil? Who is where they should not be, and have no right to be? Who has killed tens of thousands of people in their homeland, and starved their children and deprived them of proper medical care? And yet many people will fall for just such a headline, and never once stop and think of how they would feel and what life would be like if the situation were reversed. They cannot imagine running through a smoke-filled street with their dead child in their arms. That only happens on TV, reported between advertisements for unaffordable new prescription drugs by news anchors with strategic hair and mock expressions of concern — until it’s time for a feel-good story, when they miraculously cheer up, as if the blood had suddenly stopped flowing and peace were declared. This is what’s happening.

September 15, 2004 — Shall I write about the sixty people who were killed yesterday in Iraq, or shall I sit here and pretend to go about my business? What is my business? “None of your business.” They were killed because Iraq has been liberated. Or, as the great Rumsfeld said on TV several months ago, “Freedom is a messy business.” Ah, there we go again, with that hideous word, business. But business is what the war is all about. It is what the war is. As for my own business — hah! — I’m thinking quite seriously of raising my lemonade price from five cents to ten cents a glass. “Lemonade, mister? Oh, I’m sorry. Had I known you were busy killing people in the name of freedom and democracy, I wouldn’t have asked. Excuse me.” Really, I’ve got to find a better location. Or a better business. Hey, I know. I’ll be a writer. That ought to be easy. I can sit in my room all day and wait for the war to blow over. No one will find me here. No one will — hey! who are you? how did you get in here? I — ugh. Once again, I must apologize. It was one of my cutthroat lemonade competitors, trying to poison my supply. I use real lemons, you know. Did I mention that? I don’t use frozen concentrate. Oh, yeah, that reminds me of a good “blond” joke. A blond was staring at a can of frozen orange juice. Her friend said, “What are you doing?” and the blond said, “It says concentrate.” Ha-ha-ha-ha-ha. You see, this is what happens when you try to outlast a war that is nowhere near ending because there are too many people making too much money from it. So you go crazy. Really, you should try it some time. It feels good. “Lemonade, mister?”

September 16, 2004 — Hurricane Ivan is battering the coast of the southern U.S. This means it won’t be long until the president flies in and hands out bottled water and sandbags with his shirt sleeves rolled up. “I told you, take it of my good side.” Very well, Mr. President, as you wish. Turn around. There. Now. Bend over, please. Excellent! Oh? You’re leaving already? But you just got here. What about all these sandbags? Don’t you want to stay and help? The least you could do is check the voting machines before you leave, to make sure they are malfunctioning properly. What’s that? Your good buddies at Diebold are in charge of that little detail? I’m sorry. My mistake. Well, then, as Mario Lanza once said, I’ll be seeing you, in all the same old places. . . .

September 17, 2004 — Yesterday evening, an obnoxious-looking young man in a cheap tan suit marched up to the house and rang the door bell. When we didn’t answer promptly, he rang it again, then pounded vigorously to let us know he knew we were home and that he didn’t appreciate being ignored. Then he left. But about forty-five minutes later, he was back again, this time ringing and pounding simultaneously. Our youngest son asked me, “Aren’t you going to shred him?” When I told him I wasn’t in the mood, he was disappointed. “You can if you like,” I said. Then his brother came in and said, “I know. Why don’t you open the door but not say anything? Just stare at him.” I said that was a pretty tempting idea, and then we acted out the scene for our own amusement, our eyes getting bigger and bigger. While this was going on, the young man had leaned on the bell one last time and given up. A couple of minutes later I went out to apologize, but I couldn’t find him anywhere. I felt terrible. Then I closed the garage door and came back inside, after which Vahan cranked up his Fender ’59 Bassman, rattling the house. Shouting over the noise, I said, “Hey, how will we know if anyone comes to the door?” Vahan shrugged, but continued playing. So I went back outside, and began searching through the neighborhood for the obnoxious salesman. Had I found him I would have shredded — I mean explained to him that contrary to what he learned in school, most people don’t like having their doors hammered unless there is a fire, or a visit from aliens, or some similar development, and, further, that some people also feel it is their right to not answer the door if they don’t feel like being bothered. After circling the block, I noticed flames leaping from our roof, where an alien space ship had landed. I was about to call the fire department when several obnoxious-looking young men in cheap tan suits jumped out of our pine tree and began spraying me with cologne and trying to sell me vacuum cleaners. It was then that I realized how far-reaching the effects of Bush’s economic policies are. Because, just as I was showing them my empty pockets, a fancy space shuttle arrived bearing recruiters for the armed forces of the Intergalactic States of America. The poor aliens didn’t stand a chance. They listened excitedly to the recruiters for about fifteen seconds, then signed their lives away. Soon, everyone was gone. I called the fire department, and they came and put out the fire, and disposed of the wreckage. I thanked the men for their efforts and told them all that had happened. “We’ve seen a lot of this lately,” one of them said while he was rolling up the hose. The men left. I went back inside, wondering where it all would end.

September 18, 2004 — Someday, possibly much sooner than I think, these words will have lost their meaning. They might already have done so. On the other hand, who is to say that they won’t live and breathe for a thousand years, or even longer? But if they do, they will probably mean something else, or more, or less, than they mean now. A thousand years is a long time — almost as long as the time it has taken me to write these few sentences. And no, I don’t know where this is going. All I know is that it is going. Anything might happen, and my course will abruptly be changed. It’s raining. That means something. It means the air is fresh and cool, and that we won’t have to water anything. And that means something. It means that what we have to water won’t last much longer anyway. It means summer is over. And then there is the coffee I’m drinking, and the encouraging sounds rising from my keyboard, and the ringing in my ears, and the fact that the gardening crew that takes care of the house next door just started a noisy leaf blower and lawn mower. What do they hope to accomplish in the rain? Being paid. There is no other reason for them to be there. Because the truth is, what they are doing is idiotic and unnecessary. But what about what I am doing? I know it’s idiotic, but is it also unnecessary? I, too, want to be paid, but being paid for a piece of writing is a lot more difficult to arrange than being paid for raking leaves or mowing a lawn. It involves the use of several complicated formulas and equations, all of the known sciences, religions, and philosophies, the interpretation of dreams, the suspension of physical laws, the study of languages, history, and music, the observation of ants and termites, and drinking huge quantities of water. Without the water, all else goes for naught. I should also mention Muscat grapes, which are to me one of the earth’s dearest commodities. Last year, we had none. I worked an entire year without Muscat grapes. A few days ago, we found some at a local fruit stand. They were small, of course, and not quite as sweet as they should be, but they were Muscats. I ate a small bunch last night, grinding up the smaller seeds, spitting out the larger ones. They were the first and only grapes I have eaten all year, because I refuse to eat grapes from the grocery store, which are stacked in ignorant heaps and sweating in plastic bags. Is my writing necessary? I believe it is, but is it even for me to say? And yet I have said so, many times, and will probably continue to say so. Why the heck shouldn’t I say so? If I didn’t feel it was necessary, I wouldn’t be doing it. And yet, at the end of the day, I am often deeply disturbed by my lack of accomplishment. As I survey the wreckage of the preceding hours, I can only shake my head in wonder. There is always so much more that needs to be done, that I feel I should take a shower, put on a pot of coffee, and start another shift. I feel I should work through the night. This in turn severely reduces the quality of my sleep. Last night, for example, from about midnight on, when I awoke from a nightmare kicking at a strange assailant, I tossed and turned and woke up every fifteen or twenty minutes. By five this morning I was crippled, and I still haven’t straightened up completely. But I did make a nice breakfast for our son, and I did get him to his iris job on time. It was a beautiful trip, cloudy and windy, and we saw a man from our general neighborhood walking past the corn field along Tepper Road. Perhaps he wondered, as I did aloud, whether the crop would ripen fully in the cool weather. This is what I do. I wonder about what people are wondering. I also wonder about myself, and the strange life I seem to be living, which is really a wonderful life, though it is fraught with peril.

September 19, 2004 — A few minutes ago, my precious bride told me about an elevator accident that took place last night in the Reed Opera House in downtown Salem. The Reed is a very old brick building with an alternating array of shops, offices, restaurants, and vacancies in the basement and on the first and second floors. The third floor is occupied primarily by a spacious ballroom with windows that look down on the street. The ballroom is frequently rented out for events, last night’s being a wedding reception. It seems the main elevator has been under repair, and for that reason the freight elevator was being used when a dozen or so guests and the elevator operator didn’t stop as expected on the ground floor, but continued all the way to the basement in what one passenger said was a “free-fall.” Three or four people went to the hospital with minor injuries. The elevator repairman, though, who happened to be in the building at the time, smiled at the term “free-fall.” He said that wasn’t the case it all, and that the elevator was traveling at the normal speed and simply didn’t stop when it should have, continuing instead until it reached the basement, where it had to stop, giving the passengers an extra jolt. I have ridden in the Reed’s elevators a few times myself, but have always preferred taking the stairs, because it allows one to better appreciate and experience the old building, which, if I remember correctly, is supposed to be haunted. Not only that, many years ago, a friend and I had a small newspaper office in the basement. I still remember arriving one morning to find water dripping onto my computer monitor. The ceiling wasn’t finished, and so there were several large pipes overhead. To make matters worse, the entire front wall of the office was glass that didn’t reach the ceiling, so being in the office was like being in a fish tank. When we spoke we had to do so quietly, because our voices echoed. Still, everything was great, because we were in the Reed Opera House — along with a tailor, a hair salon, a guitar repairman, and a business that helped people with handicaps find work. Unfortunately, no one ever asked us where our office was, and no one paid us a visit, except for the downtown parking police, who came in to measure the place so they could decide how much to charge us for the people who would be using the free parking spaces outside the building when they came to our “place of business.” We told them no one ever came, and since we made no money we could hardly be called a business, but we were still charged the minimum of two parking spaces, which came to about eighty dollars a year. Early on, we also received a visit from a cologne-soaked representative of the local Chamber of Commerce, who was unnaturally excited about the idea of having a hand-shaking and business card-exchanging party in our aquarium. This idea evaporated into thin air when the Chamber realized that one of the papers we were publishing was a new monthly business gazette which competed directly with one they had started, or, rather, had been roped into doing by Salem’s “local” daily. Instead of embracing our presence for the good of the area’s business community, we were treated as outcasts — a situation we relished, especially in print. These days, the Chamber still holds its hand-shaking parties, while vacancies continue to escalate in the Reed Opera House and elsewhere all over town, and places like Wal-Mart thrive. The chain-owned daily, of course, still charges exorbitant advertising rates, thereby draining the pockets of business owners desperate for customers. All in all, it is a happy formula that benefits everyone.

September 20, 2004 — Somehow, we must break free of the rat’s grasp. His foul teeth and claws have poisoned our systems, our minds. We think we think, but what we think is not what we think we think. It is what he thinks, and what he wants us to think — which is not thinking at all, but stinking. He chews corpse-flavored gum, twirls nations by the tail, has buzzards for friends, saves the flies, and throws out the ointment with the bath water. Other than that, he is a nice rat, a good, fat, rat-a-tat rat, a fancy dude of a card-playing rat, a hat rack rat with a belt buckle, the head rat who speaks through his tail. He is a rat with eyebrows, a most important characteristic, a foibling rat, a lungful of bad air rat that stifles a young century, a roasting pan full of mud and onions rat that chases ducks around the pond until they sink, then smiles at them through the window in the oven. Who is he? Who is this rat that mocks the sorrow-laden world? Who is the rat with teeth so long that they leave a lightless miner’s shaft of oily pain? Is he who we think he is? Are we really who he thinks we are — a deaf, dumb, blind multitude asleep at our watch? Or is everything and everyone something and someone else?

September 21, 2004 — If it weren’t for my work, I would have gone mad far sooner, and in a different, more dangerous way. I would not only be mad, I would be angry, and the world would be missing out on my irresistible warmth and magnetic optimism. Everyone would think I am impatient, bitter, cynical, arrogant, and opinionated, and that I see no reason to change. They wouldn’t know me as the mild, unassuming, gentle, forgiving person I am. And what a shame that would be. Yes, if it weren’t for art in general and writing in particular, I would not be sitting here today, blessing the world with my wit and wisdom. Instead, I would be clawing my way up the ladder of commerce, eating in traffic jams, and playing telephone tag with people who pretend to like me but in reality are trying to keep me from getting anywhere — and vice-versa. Truly, writing has saved me from myself, and the world from the monster I could have become. It has saved my wife and children as well, from having to cope with someone who flies off the handle for little or no reason, and who curses inanimate objects for refusing to cooperate. The peace and tranquility they know and have come to expect and rely on would be nothing more than a dream or fairy tale. But I take no credit for their happiness, or mine, or the world’s. I owe everything to art, and to my battered muse, who lies crumpled in a drunken heap in the corner. Hey — wake up, damn you.

September 22, 2004 — It was interesting to see George Served Honorably But Wasn’t There Bush speaking before the United Nations yesterday. His expression said it all. It said, “Man, these people hate me.” The smirk was temporarily gone. All he wanted to do was read his piece about how he is saving the world from terrorism by destroying Iraq and leave. Poor guy. After seeing him suffer, one can only hope he’ll be able to get in a few rounds of golf, or a make trip to his ranch. . . . In other news, our iris worker did in fact buy a twelve-string acoustic guitar with part of his summer earnings. It’s a Taylor, and truly a thing of beauty, with thrilling, rich sound. This, too, is what is happening in the world: a seventeen-year-old boy deciding a year in advance that he will buy an expensive musical instrument, and then working ten hours a day digging, cutting, sorting, and packing irises during the summer to earn the money he needs, and, finally, after trying various guitars, bringing home the one of his dreams. It is inspiring to say the least. Best of all, after two days, he is already playing the thing as if he had been doing so all along. It feels to me, and I’m sure it does to him, that a new door has opened, and that all he needs is to walk through. This is why we work, why we live — not to get ahead, or to have more than the next person, or to take over the world and control its resources. The monsters of the world, the real terrorists like the current president, will never understand this. They will never know the pleasure of productive labor that enriches the spirit and benefits all. They will know only the pain of acquisition, and the mind-numbing, spirit-killing desire for more. Greed and suffering are their inheritance. These are powerful forces, indeed. But there is still music in the world. And as long as there is, there is hope.

September 23, 2004 — Last night I read “The Cop and the Anthem,” a short story by O. Henry that was beautifully adapted for television back in the Fifties by none other than the great Red Skelton. I found the piece in another book of O. Henry’s stories that I picked up earlier this week at the library book store. The Complete Works of O. Henry runs close to 1,700 pages, and was published in 1937 by Garden City Publishing Co. in New York. On the same trip, I also bought Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls. Even though I found the aforementioned volumes within the first thirty seconds, I was in the store for a full five minutes — long enough to browse through the entire fiction section while sitting on a child-sized but very sturdy and nicely varnished wooden chair that for some odd reason is in exactly the same spot every time I visit the store. “The Cop and the Anthem” is about Soapy, a bum who, noticing the rapid approach of winter, follows his usual plan to secure lodging in the warm confines of jail. His methods are simple enough. First he tries to enter a restaurant and order roast duck, and then to be turned over to the law when it is discovered he is unable to pay. But he is thrown out as soon as he sets foot in the door. Then he breaks a store window, but is ignored by the police because “Men who smash windows do not remain to parley with the law’s minions.” Then he tries to steal an umbrella, but as another policeman approaches, it turns out that the person he tries to steal it from has also stolen it, so the thief gives Soapy the umbrella and flees. Then he decides to be a “masher,” and in full view of another policeman makes lewd and suggestive remarks to a young woman who, much to his disappointment and surprise, takes him up on the offer. Everything he tries, fails. Finally, as Soapy slowly returns to his park bench in defeat, he is stopped by the sound of beautiful music emanating from a small church. It is a captivating tune, “. . . for he had known it well in the days when his life contained such things as mothers and roses and ambitions and friends and immaculate thoughts and collars.” Following the sudden impulse to reclaim his life, he decides he is still young enough “to resurrect his old eager ambitions and pursue them without faltering.” He knows of a job, and decides to apply for it the following day. Then, while he is standing there listening to the music, he feels a hand on his shoulder. It is a policeman, and Soapy is arrested for loitering and given three months in prison. It is a classic O. Henry ending, and one that Red Skelton played to perfection as “Freddie the Freeloader.” With his painted clown face, when Freddie hears the church music, his expression is so tragically sad and full of remorse for a life ill-lived that one cannot help but recognize Skelton’s genius and personal sorrow. And such is the life of a good story, that it can not only be read and understood within the context of its own time, but that it can live and be re-enacted fifty years later, and that fifty years after that it can be read again and remembered in conjunction with what it has meant to other minds. If that isn’t enough reason to live and work, nothing is.

September 24, 2004 — The writer best able to forget is the writer best able to move on. This writer feels no need to reinvent the wheel, only the need to examine it more carefully in the light of his accidental knowledge, its natural ebb and flow. For the wheel itself is also changing, as the writer is changing, and the world’s perception of the writer and what he does, and the possible meaning of his rebellious presence. The opportunity to work is all he asks. If you give him money, he will take it, because he needs it desperately. But if you give him money with the understanding that he is not to work, he will return the money unspent. If he doesn’t, if he takes the money and quits writing, then he was not a writer in the first place, but an imposter instead. The world is teeming with pretend writers. It might be in everyone’s best interest if these pretenders were paid off and allowed to fold their gaudy tents, because doing so would save countless trees, and make it easier for real working writers to be heard. At the same time, a truly advanced civilization would never place a price tag on art. An advanced civilization would see to it that art is made freely available to all, and that everyone, young and old, has the opportunity to pursue their artistic instincts, and to be exposed to art in general. We do not live in such a civilization. We choose material things instead. We choose war. We teach our children to stifle their instincts and pursue money, then wring our hands as their healthy innocence is replaced by fear, anger, and frustration. Like father, like son. Like mother, like daughter. The fact that art survives at all shows how powerful it is, and how powerful the creative impulse is within us. Art is a healing force. We need to be healed. For whatever reasons, we have not yet realized the foolishness of our ways. We have not recognized the emptiness that lies at the heart of thinking we are republicans or democrats, or Christians or Muslims or Jews. As children, we know better. But we are afraid to be children. We would rather destroy a nation than study a butterfly.

September 25, 2004 — A fourth hurricane is on its way to Florida after killing more than a thousand people in Haiti and leaving many of its inhabitants homeless, hungry, sick, and without safe drinking water. Thousands and thousands of people are dying in Sudan in what amounts to yet another genocide — those little events the U.S. claims to condemn but regularly denies, ignores, condones, or helps to happen. The war in Iraq rages on. Thanks to the consistent backing of Israel by the United States, the Palestinians continue to suffer. And there are many other upheavals around the globe, both large and small, from which someone, somewhere, is managing to make a profit. The result: human beings are killing each other at an alarming rate, and simultaneously perpetuating the cycle of grief, anger, hunger, and revenge. This is our world. I mention Haiti because it is one of many poor countries around the world that are used by wealthier nations as international sweatshops, industrial dumping grounds, the sites of secret government prisons, or military jumping-off points. If these countries weren’t used in this manner, if the money that is spent killing and subjugating people were spent on helping them live a better life, then they would be far better prepared for natural disasters, and be better able to cope with their aftermath. If billions of dollars weren’t being spent on war, it could be spent on food, housing, medicine, and education. If people in wealthy nations like the United States didn’t think they were entitled to everything, then there would be more left for everyone else. Nothing could be more plain. And yet to most, the idea of voluntarily doing with even a little less isn’t worthy of consideration. Millions actually think poor people deserve to be poor, and hungry people deserve to be hungry — until it happens to them. What a shameful state of mind to be in. When through his selfish actions one human being denies the basic rights of another, a crime against humanity has been committed. When mothers and fathers teach and encourage their children to get ahead at all costs, a crime against humanity has been committed. The evidence is everywhere. There is so much of it that it is disregarded — the garbage cans overflowing with food, the fancy vehicles transporting one person, the frivolous waste of resources, the willful destruction of the environment, the inequalities in the legal system, the rape of the general public by wealthy corporations — the list goes on. And yet surrounded by such evidence, we still choose to continue along the same path. Sadly, many who do care still think change must come from without, rather than within. They think it will come through legislation, or by belonging to political and religious organizations and adhering to their shortsighted doctrines and dogmas, all of which are based on or furthered by fear and exclusion. It is a strange way to live, but this kind of thinking has been going on so long that it is considered right, virtuous, and honorable — and, we must remember, worth killing for.

September 26, 2004 — Much to the dismay of my loving bride, I now own an oversized European beret — the kind with a floppy crown that sags to one side, like the combs on the demented old hens that used to peck their way around our barn. It’s black, and I think it looks great. Our oldest son agrees, but everyone else thinks it’s ridiculous, out of place, or just plain stupid-looking. Our daughter said, “You look like a painter. Maybe it would be all right if you were in Paris.” I took both statements as compliments. Since Vahan said he liked it, I asked him if it was because he thought it was comical, or because he thought it looked good. He said, “Both.” Another victory. After all, if it weren’t at least a little bit comical, I wouldn’t have bought it. Hats are ridiculous anyway. In a hat you can pretend to be as serious as you like, but the fact remains, there is something perched on your head. Whether it’s a finely tailored piece of felt or a bowl of fruit makes no difference, unless the fruit happens to be real, in which case it would pay to have a strong neck. I ordered the beret from a haberdasher in Portland. They mailed it to me in a nine-by-twelve envelope. It’s made of wool, and cost eleven dollars. When I put it on, my wife frowned and said it reminded her of an old Basque man who stayed at her house once when she was a kid. He wore a beret, and she hated him. Apparently, ever since then, she has hated berets. It’s unreasonable, but completely understandable — like my decision to buy the beret, and to do just about everything else I do, including getting up in the morning. But I look at it this way: it’s better to hate berets than Basques. And if it ever came down to deciding between them, I’d take the Basques every time.

September 27, 2004 — What does it mean that I’ve yet to write an intelligent sentence this morning? It might mean this is Monday, though I like Mondays and the clean slate they represent. But as I work seven days a week and have foolishly done so for ages, shouldn’t my slate already be clean? The answer is simple: I don’t have a slate. My slate is in the basement. And I don’t have a basement, either. I like to say I do, because basements have their own charm and potential, but the fact remains, I only have a crawl-space. The same goes for my attic. There are no trunks up there, and no family secrets. There is insulation and spiders, and maybe a dead mouse or two. I live in a boring house. This house doesn’t even have a porch, which raises the question: is this really a house, or is it just a dwelling? We have a front step. It’s made of concrete. There is enough room on the step for a large pumpkin and a muddy pair of shoes. And so it’s obvious: I need to get out of this dwelling and into a real house while I can still tell what day it is. Then maybe I can have a slate all my own, and a basement to keep it in, and a porch to relax on while inhaling the perfume of honeysuckle and pondering my next move, which will be to the attic, where all sorts of fascinating objects will be stored, old phonographs, picture albums, and treasure maps. But how will this come to pass? Should I work eight days a week instead of seven? Or should I quit working altogether? Shall I go to school and learn a trade? If so, what about the trade I already have? I could be a welder, or a dental assistant, or a court reporter, or a paralegal, or a chef, or an insurance coding specialist, or any of the other things that are being advertised these days as “financially rewarding, exciting, and fulfilling careers.” Exciting? Financially rewarding? In most cases, these jobs don’t even exist. Fulfilling? Yes, I’ve always wanted to work in the closed-captioning field. It has been a life-long dream of mine. Or what about medical transcribing? “She comes in today, complaining of right-sided wrist pain.” Who knows what she will do tomorrow, the old bat. “He spent $40,000 learning to be a chef, now he bakes muffins at Costco.” So says the social transcriber, who doesn’t have a porch.

September 28, 2004 — For the last ten or so minutes, I was under the distinct impression that Vahan had already gone to work. Then I heard a noise coming from his room and thought, That’s odd. I got up and walked down the hall just in time to hear him close the front door and start his car. I looked at the clock. It was 7:35, about the time he always leaves. I thought it was later. Why? I thought I had already heard the car start, but I must have dreamed it. I’ve been sitting here drinking coffee, not really thinking anything in particular, more or less just “getting ready.” Am I ready now? It would appear not. I’ve finished most of my cup of coffee, but I don’t remember drinking it. I notice now that it tastes quite good. Maybe I should start making bad coffee. Maybe I should rearrange my entire existence. Maybe I should drink tea, or juice, or buttermilk. Usually, at times like these, the telephone rings. Why doesn’t it ring now? I don’t want it to ring, but that’s not the point. The point is, it should ring. The point is — no. Wait a minute. I was wrong again. It’s early yet. The phone isn’t supposed to ring until later. Why do I keep getting ahead of myself? That’s funny — I’m ahead of myself, but behind everyone else — or so it seems. It might be that I am so far ahead that I only think I’m behind, or vice-versa. Who are these people who keep ignoring me? Have they no manners? Have they no coffee of their own, no tea or buttermilk? Am I to go to the store for them? Am I to milk their blessed cows? Can’t they see how busy I am getting ready? I will never be ready with them ignoring me like this. The pressure is too much, simply too . . . what time is it now, I wonder? And where did this full cup of coffee come from?

September 29, 2004 — This morning I unwrapped our last bar of soap. Last night we ordered a CD from a neighbor girl who was trying to raise money for her school. “For books and things like that,” she said. “Imagine,” I said to my wife later. “There is money enough to kill people and take over their country, but not enough to buy school books.” The bar of soap should last about three days. Then we will have to buy more, or do without. After the CD arrives in about “twelve to fourteen weeks,” it is likely we will also find ourselves on yet another mailing list. Buy now and save. But in order to do that, the soap will have to be for sale at a reduced price. And, as we all know, soap, like crackers, sponges, and canned tomato sauce, is subject to wild market fluctuations. Often a trip to the grocery store turns into an all-out bidding war, with voices screaming over loudspeakers, horns blaring, and people dropping dead on the floor, having gambled on the weekly soap price and lost everything. The CD is by Johnny Cash. I don’t know whether it contains his early music or late music or both. The CD has a title, but I don’t remember what it is. The girl’s dog was sitting in the entry, smiling at us. Long before the CD arrives, we will have forgotten we ordered it. We will have forgotten within three days, about the same time our last bar of soap runs out. For fifteen dollars, which is what we gave the neighbor girl for our Johnny Cash CD, we could have bought around fifty bars of soap — assuming we were lucky, of course. But the CD isn’t important. What is important is that the girl came to our door and wasn’t refused. Granted, she knows who we are and we know who she is, but with most of the money in the country going to kill people and take over their country, there was no hesitation on our part, even though we are down to our last bar of soap. The president’s wife was in Salem yesterday. She spoke at the junior college. She commended her husband for all he has done for education. Someone should have washed out her mouth with soap.

September 30, 2004 — I never did get back to my pile of Harper’s. There is already an accumulation of drawings and letters on top, along with a folder containing notes on the Armenian translations of some of my stories, and even a package of colored pencils. I had meant to read the short story in each issue, but the stories I did read made it difficult to continue. Now I no longer care — which means I should probably take the magazines to the library and leave them in the free magazine area for someone who does care, or who thinks he cares, or who once cared and is thinking about caring again, fearing that if he doesn’t he might be unable to care when his caring is needed the most — though in my humble opinion Harper’s isn’t worth such a crisis of conscience, or even a trip to the library. I say this at the risk of sounding ignorant, because everyone knows Harper’s is a highly intellectual magazine full of progressive ideas and wry commentary. No wonder they lost me. I have enough trouble putting on my socks. What do socks have to do with the subject? Nothing at all. Is Harper’s interested in my socks? No. Of course not. What I need is a magazine that caters to people who have trouble putting on their socks. A magazine that cares about me. A magazine for the common man, attempting common things and failing miserably. A magazine for people who are confused to begin with, and who then go on to lose their train of thought. Anyway. Where was I?

March 2003 April 2003 May 2003 June 2003 July 2003 August 2003 September 2003

October 2003 November 2003 December 2003 January 2004 February 2004 March 2004

April 2004 May 2004 June 2004 July 2004 August 2004 September 2004

October 2004 November 2004 December 2004 January 2005 February 2005 March 2005

Also by William Michaelian

POETRY

Winter Poems

ISBN: 978-0-9796599-0-4

52 pages. Paper.

——————————

Another Song I Know

ISBN: 978-0-9796599-1-1

80 pages. Paper.

——————————

Cosmopsis Books

San Francisco

Signed copies available

Main Page

Author’s Note

Background

Notebook

A Listening Thing

Among the Living

No Time to Cut My Hair

One Hand Clapping

Songs and Letters

Collected Poems

Early Short Stories

Armenian Translations

Cosmopsis Print Editions

Interviews

News and Reviews

Highly Recommended

Let’s Eat

Favorite Books & Authors

Useless Information

Conversation

E-mail & Parting Thoughts

Flippantly Answered Questions