Life on the Mississippi

by Mark Twain

Reader’s Digest Edition (1987)

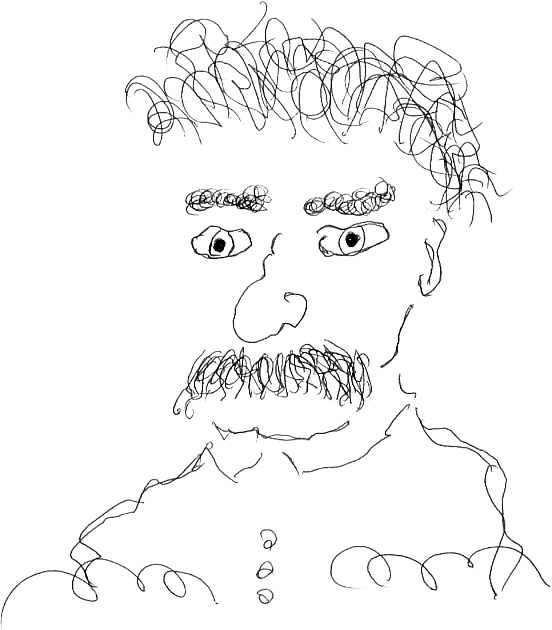

Illustrations from the original 1883 edition

Before Mr. Clemens became Mark Twain, he lived his boyhood dream of becoming pilot of a steamboat on the Mississippi River. To him, the river was a long and winding poem that rewrote itself each time he followed its path:

. . . The face of the water, in time, became a wonderful book — a book that was a dead language to the uneducated passenger, but which told its mind to me without reserve, delivering its most cherished secrets as clearly as if it uttered them with a voice. And it was not a book to be read once and thrown aside, for it had a new story to tell every day. Throughout the long twelve hundred miles there was never a page that was void of interest, never one that you would leave unread without loss, never one that you would want to skip, thinking you could find higher enjoyment in some other thing. . . .

At the same time, the science of piloting was so exacting and so demanding that learning it seemed impossible, and in fact was impossible to some who tried. It wasn’t enough merely to observe; it was necessary to record:

. . . First of all, there is one faculty which a pilot must incessantly cultivate until he has brought it to absolute perfection. Nothing short of perfection will do. That faculty is memory. He cannot stop with merely thinking a thing is so and so; he must know it; for this is eminently one of the “exact” sciences. With what scorn a pilot was looked upon, in the old times, if he ever ventured to deal in that feeble phrase “I think,” instead of the vigorous one “I know!” One cannot easily realize what a tremendous thing it is to know every trivial detail of twelve hundred miles of river and know it with absolute exactness. If you will take the longest street in New York, and travel up and down it, conning its features patiently until you know every house and window and door and lamppost and big and little sign by heart, and know them so accurately that you can instantly name the one you are abreast of when you are set down at random in that street in the middle of an inky black night, you will then have a tolerable notion of the amount and the exactness of a pilot’s knowledge who carries the Mississippi River in his head. And then if you will go on until you know every street crossing, the character, size, and position of the crossing stones, and the varying depth of mud in each of those numberless places, you will have an idea of what the pilot must know in order to keep a Mississippi steamer out of trouble. Next, if you will take half of the signs in that long street, and change their places once a month, and still manage to know their new positions accurately on dark nights, and keep up with these repeated changes without making any mistakes, you will understand what is required of a pilot’s peerless memory by the fickle Mississippi. . . .

The exceptional thing about Mark Twain is that he not only succeeded in memorizing the entire river, but in memorizing the faces, voices, lives, and stories of the people who worked in the bustling pre-Civil War river trade, and of those who lived and toiled along the river’s ever-changing banks. The same memory that made him a top-notch pilot later helped make him one of America’s best and most enduring writers.

Everything readers of Twain have come to admire and appreciate about his writing can be found in Life on the Mississippi. There are the pleasantly familiar scenes from his boyhood, the great sense of humor, the wit, the sarcasm, and the intelligence. Nothing is sacred but the truth itself. No political or religious institution is safe, no sovereign entity is above approach, and hypocrisy is an ongoing target. Meanwhile, throughout the book, there is a quiet, sympathetic understanding of the underdog, as well as a brooding sadness that isn’t spelled out, but felt. The loss of his brother in a steamboat accident is written gently and beautifully, and helps the reader realize how deeply the man was touched by sorrow.

Generally speaking, the first “half” of the book begins by describing the river in historical and geographical terms, and is about Mark Twain learning the river and becoming a pilot. The second “half” is about the author’s return to the Mississippi after a twenty-one-year absence. What he finds at that time is remarkably different than what he remembers. The railroad has all but replaced river commerce; where once were boats jostling at the shore near busy towns for two-mile stretches now is lazy silence; islands have become attached to the land; towns have disappeared, or have migrated from one side of the river to the other, in the process changing states and jurisdictions; and parts of forests have been uprooted and washed away. Knowing the restless Mississippi as well as he does, these things he can accept. What Twain laments is the loss of a culture defined by ruggedness and a quick-witted individualism that made life on the river such a colorful, entertaining affair.

Partly because he recognizes their value and partly because he can’t help himself, the author preserves and re-tells many of the stories and tall tales he heard during his time as a pilot. He also includes Indian legends, as well as contemporary newspaper articles recounting floods and disasters, and provides even more material in an appendix. The book also includes an early review of Life on the Mississippi written by Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904) that appeared in May 1883 in the New Orleans Times-Democrat.

In closing, I would like to include a passage that sums up Mark Twain’s explanation of how he came to choose his pen name, and the importance he attached to it. Most readers know “mark twain” is a term of measurement that means “two fathoms.” What some might not know is that Samuel L. Clemens was not the first to use the name, and that a highly venerated pilot from the earliest days of steamboating sent river reports to the newspapers and signed them “Mark Twain.” Once, when the author was a cub reporter, he made light of the old pilot’s contributions by mimicking his stiff, un-literary style, only to hurt his feelings so badly that the pilot never wrote again — a heartbreaking development the younger Clemens profoundly regretted. Later, when the pilot died, the author assumed the use of his pen name with the goal of doing it the honor he felt it deserved. Says Twain, “I have done my best to make my pen name a sign and symbol and warrant that whatever is found in its company may be gambled on as being the petrified truth.”

After reading Life on the Mississippi, I believe him.

Back to Favorite Books & Authors

Also by William Michaelian

POETRY

Winter Poems

ISBN: 978-0-9796599-0-4

52 pages. Paper.

——————————

Another Song I Know

ISBN: 978-0-9796599-1-1

80 pages. Paper.

——————————

Cosmopsis Books

San Francisco

Signed copies available

Main Page

Author’s Note

Background

Notebook

A Listening Thing

Among the Living

No Time to Cut My Hair

One Hand Clapping

Songs and Letters

Collected Poems

Early Short Stories

Armenian Translations

Cosmopsis Print Editions

Interviews

News and Reviews

Highly Recommended

Let’s Eat

Favorite Books & Authors

Useless Information

Conversation

Flippantly Answered Questions

E-mail & Parting Thoughts

More Books, Poetry, Notes & Marginalia:

Recently Banned Literature

A few words about my favorite dictionary . . .