The Conversation Continues

To add a message, click here, or on any of the “Join Conversation” links scattered along the right side of the page. I’d rather you use your real name, but you can use a screen name if you prefer.

To return to Page 1 of the forum, click here. For Page 2, click here. For Page 3, click here.

For Page 4, click here. For Page 5, click here. For Page 6, click here. For Page 7, click here.

For Page 8, click here. For Page 9, click here. For Page 10, click here. For Page 11, click here.

For Page 12, click here. For Page 13, click here. For Page 14, click here. For Page 15, click here.

Page 16 Page 17 Page 18 Page 19 Page 20 Page 21 Page 22 Page 23 Page 25 Page 26

Page 27 Page 28 Page 29 Page 30 Page 31 Page 32 Page 33 Page 34 Page 35 Page 36

Page 37 Page 38 Page 39 Page 40 Page 41 Page 42 Page 43

To return to my December 2002 Barbaric Yawp interview with John Berbrich, click here.

To read our original 2001 interview, click here.

William Michaelian: Okay, I give up. On Henry Miller, I mean. I read the first seventy pages of Tropic of Capricorn, and just don’t seem to have it in me to go on. Maybe I’ll try another of his books later, maybe not. But so far, nothing he said seemed truly necessary — or, for that matter, even all that sincere.

John Berbrich: Sorry about the rental thing, dude. It’s just that I was so excited, considering the possibilities of our art school & the interviewing of derelicts, that it slipped my mind. You mentioned all those great schemes of ours, yet to date we’ve accomplished exactly zilch. What are we, Willie, losers? We’ll never get anywhere....

William Michaelian: You mean having the ideas isn’t enough? There’s more to it than that?

John Berbrich: I think the Greeks called it praxis — it means something like to actually do something, rather than merely theorizing about it. Of course, if you induce someone to accomplish the task for you, I guess it still counts. And it wasn’t going well w/ the derelicts anyway — they all wanted healthcare packages & 401-K savings plans. So I suppose we’re back to square one, just you & me, buddy.

William Michaelian: Good. I propose that we begin — again — by launching a new magazine called Praxis. And that we feature the writings of derelicts. What better way to prove our good intentions?

John Berbrich: I approve of the name Praxis. How do you propose to get the word out to local derelicts, though? And what’s this about good intentions? I think we’re talking about two different schemes.

William Michaelian: To tell you the truth, when I said good intentions, I wondered what I meant by it. But it sounded good. As for the derelicts, we could try living as derelicts ourselves, except that we’ll carry miniature tape recorders and actually record the content of the magazine, then transcribe it, print it up, and become lunatic heroes of a new publishing revolution. Or is that approach a little too practical for your taste?

John Berbrich: Well, nothing’s too practical for me — theoretically, at least. Not only should we publish these oracular utterances on paper, but we could also release audio editions — like on cassette tape or CD’s. And broadcast them over the sound system of humongous shopping malls. The effects would be incalculable. We could have a nation of derelicts within a month.

William Michaelian: A truly inspiring thought. I hate to say it, but this would also make a great documentary. Derelict Nation: The Story of Praxis and the Two Men Who Changed the Face of America. Something along those lines.

John Berbrich: Now I’m inspired. So how’s the website for Praxis coming along?

William Michaelian: Quite well. It’s in the developmental stage — with an emphasis on the mental.

John Berbrich: Well, I suppose developmental is better than sentimental or detrimental. But we need to try something different, Lord William — everybody & his dog has a website. We require a new & utterly remarkable approach. An act bold, brazen, untried throughout all of mankind’s spotty history. Your Derelict Nation is pure inspiration. Hey, that rhymes!

William Michaelian: Another good sign. I’ve never heard a project referred to as being in the sentimental or detrimental stage, although obviously a project can be. But I’ll do my best to avoid it, no matter how much liquor it takes. For sure, the website will never be done. No two visits will be the same. For starters, we’ll use sound, video, handwriting specimens, 3-D cigarette butts, gum wrappers, broken bottles, and wine-soaked blankets — pages superimposed on pictures of alleys, gutters, dumpsters, steaming grates — text that glows and then fades until it is replaced by more glowing-fading text. Press a button on an interview page and a printed version is quickly made, then delivered by a derelict to the visitor’s address.

John Berbrich: We have to work food into this too. Do you think you could rig up something whereby the patron at home orders say a cheese & hummus bagel & then — presto! — it’s delivered electronically? Could you devise some method of online home delivery? You’re a smart guy, Willie.

William Michaelian: Ha! — sure I am. The truth is, I rarely get past the temperamental stage. But let me think a minute. . . . Okay, how about this: would you settle for hot coffee in a styrofoam cup?

John Berbrich: Yeah, except styrofoam’s not environmentally friendly. How about one of those heavy paper cups w/ the extra-heavy paper holder?

William Michaelian: I don’t know. This is beginning to sound like Starbuck’s. But maybe that’ll work if the cups are half full, and if the coffee is cold and contains a few leaves or crumbs.

John Berbrich: What are you — a socialist? Everyone is entitled to a half-cup of cold coffee, Comrade. You might be right, though; I think we’re losing touch w/ our original vision. Which was what? Oh yes — something to do w/ art, I believe?

William Michaelian: Yes. As I recall, we were going to interview delinquents. Or was it

dilettantes?

John Berbrich: Yes, one or both of those — in dirigibles. I can’t remember why we wanted dirigibles. I don’t know if wireless internet would work up there. And now the coffee’s cold. Might as well sing one of my favorite songs...: “What’s it all about, Wil-lie...?”

William Michaelian: Glad to see you’re happy. I’ve been concerned about you. How are the wife and kids? And your dog. Have you taken any walks to the cemetery lately? What was his name? Machu Picchu?

John Berbrich: Close. Bongo Macho. At least that’s what I call him; he has many names. We’ve also gotten a puppy, Trixie Vixen (named her myself). She’s about five months old. We’re thinking of mating them — they’d have beautiful pups. Haven’t been up to the cemetery lately, but we did take a walk tonight. Had about two or three inches of heavy wet horribly sloppy snow today. Trees are bent way over, crossing the road at some points, glaring garishly in the streetlight’s illumination. A very nice time was had by all.

William Michaelian: Sounds like it isn’t all that cold, then. There was an early snow when my brother and I were in Armenia in 1982. It was October, and the trees were loaded down, their fall colors showing through the white. In a couple of days the snow was gone and autumn resumed. Trixie Vixen, eh? I didn’t know you went in for arranged marriages.

John Berbrich: Well, in this case it’s working out very well. The two are pretty much inseparable. If you are interested, we’ll be selling pups in the spring — if Bongo can figure out what he’s doing. A little over a year ago, a peevish female named Bitsy stayed w/ us for a week. Poor Bongo was definitely interested, & he knew he was supposed to do something, but he just couldn’t quite figure out what it was.

William Michaelian: Poor guy. No doubt Bitsy’s peevishness threw him off. But it’ll be different with Trixie Vixen. Long ago, when I was still in high school, we had a German shepherd that had pups — eleven of them. She ate four, soon after they were born.

John Berbrich: Ooooo. That’s harsh. Well, realistically, eleven pups is a lot to take care of. I once read a science fiction novel by Michael Bishop — we’ve spoken of him before — which takes place on some faraway planet. The females of this indigenous hominid species always give birth to twins. Then the healthier of the babies eats the scrawny one, insuring that the healthier survives & starts off life w/ at least one good solid meal.

William Michaelian: How cheerful. I wonder — were there instances when both infants were healthy? And if so, what then? I think with some kinds of birds, the toughest hatchlings make short work of their weaker siblings. Thank goodness such things never happen among us humans. Instead, we spare each other for violence later, not to mention psychological torment. Interesting.

John Berbrich: You mention the birds. I read an article about that very subject, many years ago, in Natural History Magazine. I think that the birds were Boobies living in South or Central America, but I could be wrong. The study revealed that an imaginary safety zone exists around the Booby nest. I don’t recall the figures, let’s says it’s 10 feet. The baby birds push their siblings out of the nest; the mother retrieves them, returning them to the nest unless they are pushed beyond that critical radius point, the hypothetical 10 feet. Beyond that, the mother leaves them to die. Survival of the pushiest, very Darwinian.

William Michaelian: Amazing indeed. And just think how long these things have been going on. What a planet. Creatures hibernating for years, frenzied life-cycles, flowers attracting insects, whales singing, drunks arguing with waiters at sidewalk café tables — it’s endless.

John Berbrich: It is astounding, the sheer colossal enormity of it. In a sense the real poet loves it all & wants to sing & to celebrate. It almost makes you want to laugh or cry — our huge magnificent world, & we are, each of us, a tiny part of it — a drop in the ocean, a molecule on Jupiter. Humbling & inspirational together.

William Michaelian: Yes — everything is made of the same stuff, in different combinations. That’s what makes our attitude toward the planet and each other so tragic. People are afraid to see themselves as something small, or dependent. We want to be in control, no matter who or what it hurts, even when it’s obvious that we are hurting ourselves.

John Berbrich: I know. What’s the answer? What’s the question? I think that about the best you can do is to lead a good life & hope that you can influence others for the good. Spread that good mojo.

William Michaelian: It is. As I’ve said before, people generally underestimate, or don’t recognize, the power they have to make good things happen. I’m sure the world would have gone completely to hell a long time ago if it weren’t for the countless simple, good, small actions that people take every day. I mean, don’t get me wrong, because the world has gone to hell, but there is still plenty of room for hope. Inspiration is everywhere — at least it is for those willing to be inspired. Assuming, of course, they aren’t starving, or being bombed, etc.

John Berbrich: Yeah. There are limits. Celebrate if you can, as often as you can. Write a little poem in gratitude. Share a little something. You get to work on Monday morning & people start right in, “Is it Friday yet?” Never happy, always too dry or too wet, too hot or too cold, too hard or too easy. I love books about people who want to experience the world.

William Michaelian: Just wait until you read the Odyssey sequel by Kazantzakis. Talk about experience. Or his Zorba the Greek. Another thing that kills me is when people boast about how they got away with something, how they fooled someone, or how they get by doing as little work as possible, as if work were something unclean or beneath them. And I hate the victim mentality that is so prevalent nowadays. There is an excuse for everything, and every problem you experience is someone else’s fault.

John Berbrich: Oh, don’t get me started on this one — I agree totally. No one is responsible for anything. That’s what I find so appealing about Existentialism — you are responsible for EVERYTHING. Once you start passing the buck it never stops. Poor me. Poor pitiful me. Poor you. Let’s sob together. & blame the universe.

William Michaelian: Put that way, it sounds like a big club. Membership is cheap, and when you miss one of the meetings you blame it on someone else. When you find out later your neighbor won an award, you resent him and belittle his efforts. What’s he gloating about? I could have done the same thing if I’d wanted to — that is, if I only had the time.

John Berbrich: Indeed. Every victim has his rights. Rights used to be considered like a shield, to protect you from others. Now they are a sword. I once wrote a poem about this.

Victim

They wave their “disabilities”

like banners of honor

certified victims of the universe.

William Michaelian: That’s just it — people actually take pride in their victim status and use their “disabilities” as an excuse. And then you meet someone with real problems who never complains, and who works hard to do whatever his situation will allow. I wonder why this victim mentality is so common now. Is it that we have drifted so far from our rural, pioneering, self-sufficient roots, are spoiled by convenience, and now expect everything to be done for us? Is it because there are so many of us and everyone feels hemmed in? Maybe it’s a way of striking back at a world and life that is frightening and feels out of control. And then you have television. Thanks to TV, victims all act the same. TV even tells people what’s wrong with them, and then sells them the cure.

John Berbrich: Like doctors. I remember reading old Aristotle years back. Somewhere he mentions that in his day, if you committed a crime, the fine was doubled if it was determined that you were drunk at the time. So being drunk was no excuse — you let yourself over-indulge & you have to pay the penalty. This makes perfect sense to me.

William Michaelian: It’s only logical. And nowadays there are similar laws, at least for those who can’t afford to buy their way around them. At the same time, excessive behavior sells, although what it sells isn’t worth buying. Which reminds me — how are you coming along in rehab? And when will your new book be out? Is it true, what they’re saying?

John Berbrich: Oh, Willie, you know you can’t believe a thing they say, although if you follow the tabloids & listen to late night radio you might garner a smidgen of a particle of a microbe of a kind of a half-truth. Which is a pretty good chance, all things considered.

William Michaelian: I knew you’d be frank. Now, in lieu of a commercial break, I want to share a few words by Nikos Kazantzakis on the subject of experience. The following is from an interview that took place a couple of years before he died. It’s a little story that was part of his novel Freedom or Death?

These Cretans have grown so familiar with death that they no longer fear it. For centuries they suffered so much, proved so often that death itself could not overcome them, that they came to the conclusion that death is required in the triumph of their ideal, that salvation begins at the peak of despair. Yes, the truth is hard to swallow. But the Cretans, toughened by their struggle and greedy for life, gulp it down it like a glass of cold water.

“What was life like for you, grandfather?” I asked an old Cretan one day. He was a hundred years old, scarred by old wounds and blind. He was warming himself in the sun, huddled in the doorway of his hut. He was “proud of ear” as we say on Crete. He couldn’t hear well. I repeated my question to him, “What was your long life like, grandfather, your hundred years?”

“Like a glass of cold water,” he replied.

“And are you still thirsty?”

He raised his hand abruptly. “Damn those who are thirsty no more,” he shouted.

That’s the Cretans for you. How could I not make a symbol of them?

John Berbrich: Sounds like many of the Armenians you’ve described to me, w/ that thirst & those appetites. I know some people who seem to have at least mild thirst for the experiences of life. Most other people schedule their glasses of tepid (store bought) water, never thirsting. Reminds me of lines from Tennyson’s “Ulysses,” a poem we discussed many pages ago: “I will drink / Life to the lees.”

William Michaelian: Right. Or Whitman howling in the woods. I wonder if example has something to do with it. The narrator of Zorba the Greek was inspired by Zorba’s wild crazy earthy freedom. It made him realize that there is more to life than intellect and the pursuit of security. It’s like being near a bonfire. Something primitive is awakened deep inside, and you can’t help but sing and dance. A society of people who do not thirst makes life a sad dull party. Although, I think people do thirst. They might not know it, and they might not know what they’re thirsting for, but they do thirst.

John Berbrich: That’s what Thoreau meant when he said that most men lead lives of “quiet desperation.” And that’s what Ginsberg, Kerouac, & the gang were trying to do — wake up everyone & make them howl, teach them to howl, teach them by words & by example just how to howl & that it’s okay, howling is man’s primitive & natural state. You can’t fault these fellows for trying. I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of Paul Winter, but years ago I saw him in concert — his band known back then as Winter Consort — & at the beginning he urged the audience to howl & pretty soon sure enough he had the concert hall howling like wolves, getting in touch w/ their barbaric primitive selves. It was a very cool evening.

William Michaelian: Winter Consort. Sounds familiar, but I can’t quite place them. What year was that? You describe a great scene. I’m sure you’ve heard John Lennon’s first album after the Beatles broke up. He does some pretty good howling on that one.

John Berbrich: John was imitating Yoko’s yowling, I’m sure. The Winter concert was in NYC back in the seventies, obscured by the mists of Time. By the way, today is Howie & the Wolfman’s terrifying Halloween radio show. I’ve got lots of goodies lined up.

William Michaelian: As I’d expect. I’ll bet you guys really set the mood. What are some of the highlights?

John Berbrich: “Black Sabbath” by Black Sabbath from their Black Sabbath album. “Grave Ride” by John Lydon, formerly Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols. Macabre poems by Zacherle, the theme music from The Addams Family, “The Monster Mash,” “The Invisible Man” by Alice Pearce, lots more. We won’t have time to play all the possibilities.

William Michaelian: Who is Zacherle?

John Berbrich: When I was a kid, there was this great TV show Chiller Theatre that played all the cheesy horror flicks of the 50’s — Attack of the 50-foot Woman, The Amazing Colossal Man, The Four Skulls of Jonathan Drake, The Hideous She-Devils, The Crawling Eye, lots more. Zacherle was the host, this ghoulish character living in a dungeon, stirring a huge bubbling cauldron, talking to his wife whom he kept in a coffin, & laughing fiendishly at nothing at all. I loved that show so much.

William Michaelian: Chiller Theatre. I haven’t thought of that for years. Pretty vague. Good titles. Did Zacherle actually write poems, or did he just stand in for guys like Poe? — not that there were many guys like Poe. Hmm. “Guys Like Poe” could be a decent title, except if you read it wrong you think it’s about guys who like Poe, rather than guys who are like Poe. So forget I brought it up.

John Berbrich: Forgotten. Zacherle wrote some appropriately ghoulish poems recited over weird music, complete w/ distant howls & screams. We found a CD in the WTSC archives w/ a few of his recordings along w/ a lot of other macabre stuff. Excellent, really. If Howie got a good recording of this show I’ll send you a copy.

William Michaelian: That would be great. I like the appearance of the name Zacherle. A poem, really, in its own right. I’m guessing the ch is pronounced as an sh. At least I hope it is: Zuh-shirl.

John Berbrich: Uh, no. It’s Zak-er-ly. Rhymes w/ wackerly, a word you don’t see very often & is heck to find a rhyme for.

William Michaelian: Drat — another disappointment.

Wackerly Zacherle

was back early —

Surely you remember.

John Berbrich: I kinda remember that from my youth, but I think that only the girls sang it while they were skipping rope. Hey, speaking of Zacherle, today’s Halloween — what are you gonna be?

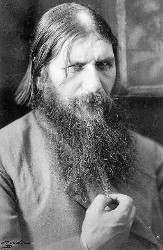

William Michaelian: Rasputin, as usual. And you?

John Berbrich: A guy pretending to be a guy giving out candy. It’s my favorite. Homemade. And I get to sample the treats. How many trick-or-treaters do you get each year?

William Michaelian: Mobs. Dollface just filled a big tub with candy. I told her to leave the porch light off and we’d eat it ourselves. Homemade candy? What kind do you have?

John Berbrich: No, no, no. My outfit is homemade. My regular guy costume. The candy is store bought. But Nancy found these cool new sweet things, body parts, bloody fingers, eyes, stuff like that. Oh, they look good. Candy, of course.

William Michaelian: Sounds very appetizing. I see you take Halloween seriously. I mean, even a homemade regular guy costume — you’re going all out. Have you tried wearing it at other times during the year? Out of context, something like that could grab a lot of attention.

John Berbrich: I try to wear a regular regular guy outfit. Most people can’t tell the difference between the outfit & the costume.

William Michaelian: Let me see if I understand this. You regularly wear a regular regular guy outfit. But you also have a regular guy costume, or outfit, which is homemade, and which you wear regularly on Halloween. Is that right?

John Berbrich: Yes, that’s exactly it. But tell me more about your Rasputin outfit.

William Michaelian: Okay. No special clothes. Just my usual old black sport coat, black pants, and black shirt. Whenever I want to be Rasputin, I skip bathing for a couple of weeks. When my hair is plastered to my forehead and I reek properly, I stand on the corner in front of the Bank of America building downtown and hypnotize passersby with my stare.

William Michaelian: Okay. No special clothes. Just my usual old black sport coat, black pants, and black shirt. Whenever I want to be Rasputin, I skip bathing for a couple of weeks. When my hair is plastered to my forehead and I reek properly, I stand on the corner in front of the Bank of America building downtown and hypnotize passersby with my stare.

John Berbrich: Rasputin is one of those amazing & oddball characters in history. I remember reading once that to kill him the conspirators had to shoot him, strangle him, poison him, & drown him, I’m not certain of the sequence. One tough guy. You do resemble him a little.

William Michaelian: Why, thanks. I do, don’t I? Rasputin was something else, but exactly what is hard to say — possessed, brilliant, magnetic, wicked, filthy, disgusting, single-minded, resourceful, an opportunist, a product of his time, and, as you said, incredibly tough, as if he had passed through many forms of torture and there was nothing left to faze him. A thorny, hallucinogenic weed.

John Berbrich: That’s a good picture of you, Willie. In fact, you look exactly like Rasputin in that shot, although you appear to be picking something out of your beard. A bit of lunch, perhaps?

William Michaelian: Nope. Halloween candy. But lunch is always a possibility, as well as various creatures and pests. Be sure to click on the picture. Inspiring, isn’t it? Wouldn’t I make a great Sunday school teacher?

John Berbrich: You’d put the fear of eternal Perdition into youngsters, that’s for sure. Hey, did I tell you that we ended up w/ exactly 48 trick-or-treaters? We did. And two smashed pumpkins at the four corners downtown. Imagine going to Mr. Rasputin’s house on Halloween night — only the bravest kids would dare it.

William Michaelian: I like it. Every town should have a Mr. Rasputin. He’d be old, but nobody would know how old, and he’d be surprisingly nimble, and quick with his hands, surprising kids and dragging them in from the shadows. A retired gravedigger. Shovels leaning on his porch, well shined from recent use. Speaks with a heavy Russian accent, once a seminarian, still wears the coat he was wearing when he was banished from the monastery. Moths in the lining — lots of moths, and miscellaneous tattered pages torn from the Book of Hours. Lives with an incredibly old woman, maybe his mother, maybe his daughter, maybe his wife. Survives on raw eggs, tea, onions, and the coarse black bread the woman makes from sawdust cured in molasses.

John Berbrich: Willie, you’re scaring me. That diet sounds positively hideous.

William Michaelian: Of course it does. But that’s what makes him so hard to kill.

John Berbrich: Willie, we — I mean, you — have a gold mine here. You know how popular diet fads are. Well, here it is — Dr. Willie’s Rasputin Diet. Guaranteed to make you hard to kill. Riches & fame. Dames. Oprah. Larry King. Buy the book. Then buy the CD. Then buy the DVD. Then see the movie. We’ll be rich!

William Michaelian: Again. We’ll have the biggest sawdust and molasses contracts in the country. The onion farmers will all buy Cadillacs. Best of all, everyone will look like Rasputin and his mother.

John Berbrich: And live for a long time. I would not mess w/ anyone that looked like Rasputin. I’ll tell you though, I like molasses & onions, although I’m not keen on sawdust. I’ll stick to my usual diet. I’m a carnivore.

William Michaelian: A legitimate, no-nonsense approach to survival. I’m sure Rasputin sacrificed a sheep or two in his day. It’s easy to picture him on a bleak November day in a Russian Orthodox churchyard, standing before a broad flat bloodstained stone, butcher knife in hand. Behind him the church cemetery, and further in the distance a stand of birches, now bare. Strong fingers, working without hesitation. Stealing glances at the peasants’ daughters.

John Berbrich: A chilling scene. I love looking at pictures of the old Russian authors. Chekhov aside, they all look like wild men: Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Gorky. Rasputin fits right in w/ this crew. Can you imagine him cracking a smile. That would worry me; I’d vacate the room immediately. But what would Rasputin write, do you think?

William Michaelian: Nothing very long, I would guess. Maybe some dark, vodka-fueled poetry along the lines of Rimbaud or Baudelaire. A revolutionary tract or two. A lewd and comical account of Genesis.

John Berbrich: I was thinking of something perhaps more along the lines of the Marquis de Sade, w/ maybe a mystical turn. Cruel & ethereal simultaneously.

William Michaelian: Good combination, especially considering Rasputin’s reputation with the ladies. But didn’t I also read, somewhere along the line, that Rasputin was in fact quite a thinker and a priest? It might well be we are underestimating him.

John Berbrich: I thought that calling Rasputin cruel & ethereal was a compliment. I think that he may have been some kind of priest (no guarantee of virtue) but haven’t ever heard him referred to as a thinker. I’ll have to investigate this further.

William Michaelian: In that case, the thing to do is to travel to the Rasputin Center in Siberia, Indiana. Or to the Shoknovostokayava Institute in Vladivostok, Iceland. Maybe I’ll go with you. I’ve long wanted to take the trips myself, although some say I’ve already been.

John Berbrich: Maybe someday. That would be cool. But for now...I’ve got this book last Christmas & I haven’t gotten to it yet. It’s called The Most Evil Men and Women in History. Guess who’s in there? Our old friend Rasputin.

William Michaelian: Really? So we can save the travel expenses. By the way, it turns out I misspelled Shoknovostokayava. It’s supposed to be Shoknovostokayavabirsk. Not that it matters. Tell me a little about the book. Who else is in there? Anybody we know?

John Berbrich: Our man Rasputin is in w/ some real sweethearts. Caligula. Idi Amin. Nero. Pol Pot. Torquemada. Hitler. Vlad “The Impaler” Dracula. Stalin. Ivan the Terrible. Great names. In the interest of equality, there are even a few women in here. Very progressive. But let me look a little more closely....

William Michaelian: Careful — one of them might reach out and get you.

John Berbrich: Thanks. Says here that they castrated Rasputin when they killed him. Gross. Also says he was “semi-literate.” His name was actually Grigori Yefinovitch Novykh. Because he was “rowdy and lascivious, a drinker, a brawler and a thief,” people took to calling him Rasputin, from the Russian word rasputnik, meaning libertine or debauched person. Are you w/ me so far?

William Michaelian: Yep. Very interesting. And rasputnik is almost identical to Sputnik, the name of the Soviet Union’s first satellite. Go on.

John Berbrich: Well, for some reason unknown to me Rasputin went to visit a monastery in the Ural Mountains, & experienced some kind of epiphany. He discovered that he had the ability to calm distressed people & to predict the future. At this point he discovered the Khlysty, an obscure Christian sect which supposedly believed that it was only by sinning that one could be saved. “Stress was laid on penitence, but also on ecstatic communal rites and dancing, often culminating in wild sex orgies involving the entire group.” No address or website is given. Rasputin built a cabin in a remote region & there seduced hundreds of young girls. It was then that Rasputin began to consider himself a holy man.

William Michaelian: See? I told you he was a thinker. It sounds like the old chicken-or-the-egg thing. To be cleansed, one must repent, and yet repentance can come only after one has sinned. Therefore, it is necessary to sin. And since you must sin, you might as well do it in style.

John Berbrich: There is some logic to that. Anyway, Rasputin traveled around Russia, “preaching and fornicating,” offering himself as both the means of temptation & by implication the vehicle to salvation. Apparently he developed a “flock” of followers, mostly women. It says here that Rasputin was blessed w/ “immense willpower, great physical presence and strength, natural wit and peasant’s cunning,” as well as “an almost miraculous intuition.” A magnetic, charismatic character. In 1903, this shaggy figure arrived in St. Petersburg where he joined the St. Petersburg Theological Academy.

William Michaelian: What a background. How old would he have been by then? Did he become a priest, or did they give him the boot at some point?

John Berbrich: At this point in the story, Rasputin is in his early 30’s. He attracts a large group of bored noblewomen, whom he romances “quickly and brutally.” He cures a woman who had languished for a time in a coma. She is an intimate friend of the Czarina Alix, whose son Alexei suffers from a strange malady — bleeding from the navel. Rasputin cures the lad, & as a consequence is brought closer into the household, a trusted adviser to the Czar & Czarina. Many nobles & officials warn Nicholas & Alix of Rasputin’s history of evil but they will not listen. This brings us to the year 1907.

William Michaelian: This is a great story. I think I recall that Rasputin was finally killed in 1916. That would leave him nine more years. No doubt he took advantage of them.

John Berbrich: Well, let’s see. Following the end of the Russo-Japanese war in 1905, a Russian parliament is established. Peter Stolypin becomes Prime Minister a year later. Stolypin is an enemy of Rasputin’s & banishes him from the country in 1907, apparently over the protests of the Czarina. Rasputin leaves St. Petersburg, embarking on a journey to Jerusalem; I can only conjecture about his activities in the Holy Land. In 1911, Stolypin is shot during a performance at the Kiev Opera House; the assassin is executed before a full inquiry can be made. A year later, Alexei is injured, seriously enough for death notices to be drawn up. The Czarina telegraphs Rasputin, who wires back: “Do not grieve. The Little One will not die.” In only a couple of hours, the temperature drops & the bleeding stops. Rasputin has somehow done it again & is called back to Russia.

William Michaelian: Wow. You can’t blame the Czarina for wanting him around. And of course a pilgrimage to Jerusalem only adds to his mystique.

John Berbrich: When he returns, wild stories of “vast debauches” spread through the capital. Get this: “Crude cartoons were passed around portraying Rasputin emerging from the naked Tsarina’s nipples to tower over Russia, his wild eyes staring from a black cloud of hair and beard. Gambling dens used playing cards in which his head replaced the Tsar’s on the king of spades. A caricature in the form of an icon showed him with a vodka bottle in one hand and the naked Tsar cradled like the Christ child in the other, while the flames of Hell licked at his boots and nubile women, naked apart from angels’ wings and black silk stockings, flew about his head.” In 1914 a peasant woman stabs Rasputin in the stomach but the blade seems to cause little damage. Then the Great War arrives.

William Michaelian: He probably cooked it up just for the atmosphere. You know, listening to this, I can’t help wondering how Rasputin would have been received in this country. Had he shown up at the White House, Teddy Roosevelt would have said, “Who is this freak? Get him out of here.” Or he might have been thrashed in an alley, or beaten up in an Irish bar. What fine entertainment he provided in St. Petersburg, though — a real morale-boost for the common man. Hmm. For some reason, I just remembered the great artwork on Jethro Tull’s album, Aqualung.

John Berbrich: Great cover. Excellent music too. Anyway, the Great War is here. A mob destroys the German Embassy in St. Petersburg. Apparently, Prime Ministers & Ministers of the Interior have been selected under the guidance of Rasputin, heavily aided by bribes. Over the next two years, the government goes through four Prime Ministers & six Ministers of the Interior. Here the action becomes vague. Rasputin appoints officials for strange reasons — like a great singing voice — & everything seems to be collapsing. Eventually, in 1916, a plot is hatched to kill Rasputin & save Russia. Prince Yusupov, a transvestite, tells Rasputin that a meeting has been arranged between him & Princess Yusupova, one of the most beautiful women in town. Rasputin can’t wait. The assignation is at a Palace beside a river. Rasputin’s cakes & drinks are poisoned w/ potassium cyanide, but these toxic delicacies have no effect. The Prince pulls a revolver & shoots Rasputin, who goes down. The conspirators begin to rejoice, then Rasputin gets up. He stumbles out a side door. The conspirators give chase, & shoot him in the head & the back. Even this does not kill him. They then tie his hands over his head & dump him under the river ice. This finishes our old friend. In July 1918, the Czar’s entire family is assassinated.

William Michaelian: Poor Rasputin. An innocent man, cut down in the prime of life. And all he wanted to do was help. A healer of children, a gentle soul who believed in love and salvation. I will forever picture him sitting on a park bench in St. Petersburg, spitting out pieces of his broken luck. Thank you, my friend, for relating his tragic tale. I still don’t see why he’s counted as one of the most evil men in history. I wonder how he’s treated in Russia’s history books.

John Berbrich: I have this 648-page opus by Basil Dmytryshyn, A History of Russia. Dmytryshyn calls Rasputin an “immoral, uncouth, semi-literate, unordained religious teacher.” He goes on to say that Rasputin became a “source of intrigues, scandals, corruption, and unsavory rumors that greatly undermined public confidence in the dynasty and accelerated its downfall.” He later says that “Rasputin ably assisted the Empress in accelerating the developing chaos.” I agree w/ you — I’m not sure just how evil all of this activity is. Imprudent, certainly. As you suggest, he is a sort of Aqualung figure, one blessed w/ devilish charm & that blazing sensual charisma. I should note that The Most Evil Men and Women in History was written by Miranda Twiss.

William Michaelian: Two questions: well, one, really. When were the books written?

John Berbrich: Ms. Twiss’s book was published in 2002. The History of Russia appeared in 1977. The former is written in a rather sensationalistic manner, while Dmytryshyn’s work is scholarly but not dull, an excellent textbook.

William Michaelian: I might be mistaken, but the first description of his that you give seems to indicate that Dmytryshyn didn’t hold a very high opinion of Rasputin’s “genius.” The whole subject, though, is very interesting. I tend to think that the so-called monsters of history are really a product of the people, and that they blossom into monsterhood at least in part because they have the people’s silent assent, or ignorant approval, or whatever it might be called. Meanwhile, you have to wonder just how many children Rasputin helped bring into the world. What a history that would make, if one were able to track each of them down and find out what became of them.

John Berbrich: That’s true. A good idea for a huge novel. I was wondering about the sexual diseases he was contracting & spreading around. You’d think someone would have been infected w/ something. He did seem to have some kind of knack, Rasputin did, along the lines of a faith healer. That is such a strange story. Well, I enjoyed that excursion into the unknown, how about you?

William Michaelian: I think it’s wonderful. We should definitely do it more often. Biography naturally dwells on the high points, low points, and defining moments of its subject, but in this case, as always, I find myself wondering about the daily life of the person in question — the quiet unrecorded moments, his habits, his thoughts, his meals — everything. His unpainted portrait, so to speak, made while he wasn’t looking, when he thought he was alone.

John Berbrich: Hard to imagine Rasputin folding clothes & feeding the cat. But you’re right, of course — we wonder. Say, have you heard of the black playwright Suzan-Lori Parks? I read an article about her recently. A couple years ago she began writing a play every single day. Reminds me of your short story writing adventure. Anyway, she kept it up for a whole year, 365 plays in 365 days. The majority of these are short, of course. And starting today, November 13th 2006, nearly 700 theatres in over 30 cities began the staging of these works. Parks is no newcomer, having won the Pulitzer Prize for her 2001 drama, Topdog/Underdog. Quite a project. I can’t imagine writing a shopping list every day for a year, much less something creative.

William Michaelian: Oh, you should try it sometime. It’s a great challenge, and you learn all sorts of strange things about yourself. And don’t underestimate that shopping list idea. Each day you can add a single item, and that item will serve as inspiration for the next, not unlike the monopoems we’ve talked about — or even the stereopoems. I might even try that myself. So far, my record for consecutive days of work on the same project is 730. The result is the two-year journal One Hand Clapping, which rings in at nearly a quarter of a million words. Suzan-Lori Parks — I’ve heard of her and her prize-winner, but I’m not familiar at all with her stuff. I’d really like to see what she came up with in that year-long project.

John Berbrich: I haven’t read her stuff either, yet I admire anyone w/ the determination to work that hard. I do like the shopping list idea. Aisles are so different — compare aisle 6 w/ the beer & chips to aisle 4 w/ the pet food & cleansers. A totally different take on life. Well, at least a totally different focus. Some aisles I never go up. And I always wonder what’s going on in the backrooms...

William Michaelian: Shirtless, broad-backed, sweating men unloading gigantic sacks of flour and grain. Gamblers and loose women. Back in the Thirties, my father’s aunt and uncle ran a little grocery store in San Clemente. In one of our old family albums, there’s a picture of them in their aprons near some low shelves. The entire store could fit in one of today’s supermarket aisles.

John Berbrich: I hitchhiked through San Clemente in 1975. All I remember is a palm tree, green grass, & a clear sunny sky. I missed that store by about 40 years.

William Michaelian: What a coincidence — that palm tree is exactly where their store used to be. One story they used to tell about those days was how there were house lots available for only five dollars, but they never could come up with the money. Instead, they’d pose as prospective buyers and ride around with a real estate salesman on Sunday afternoons so the guy would buy them lunch.

John Berbrich: Good story. I love hearing anecdotes like that — people making the best of what they’ve got & having a good time doing it. You seem to have a family member for every situation.

William Michaelian: Or who was the cause of every situation. Have I mentioned the uncle who used to lie down on the streetcar tracks in Fresno when he was a kid? When the streetcar came grinding to a halt so as not to hit him, he’d jump up and throw rocks at the window, then run off. This was before his stint in reform school, and before he served as a court reporter in the Japanese war crimes trials, and before he tried out as a tenor for the Metropolitan Opera, and before he ran a semi-fictitious uranium mine.

John Berbrich: No, you haven’t mentioned him yet. Sounds like a colorful character. So that’s where you gained your vast knowledge about mining that we were punning w/ a page or two ago. Uranium, huh? Do you have any left?

William Michaelian: None ever materialized. But for a time, his operation was a great investment opportunity. I should also mention that he was the same height as his sister, my grandmother — five feet. Kind of hard to imagine him in a lead role at the Metropolitan. Easier to picture him being shot from a cannon.

John Berbrich: Yes, or tossed like a dwarf. Sounds like a resourceful fellow. Didn’t by any chance leave behind a thick moldering collection of memoirs? Would make for some fascinating reading.

William Michaelian: No, but he was certainly a good enough storyteller. Unfortunately, he died much younger than his brothers and sisters. In fact, two sisters are still around — one is eighty-eight, the other is ninety-four. Three or four years ago, my brother and one of my father’s cousins paid the eldest a visit and had her talk about the old days into a tape recorder, which she was only too glad to do. She’s the one who had the grocery store. On the tape she tells stories about the family when they were still in the Old Country, including one about the death of an infant sister after a tragic accident, and one about her grandfather, who was drowned by Turks for his revolutionary activities, and other horrific tales from the dark days leading up to the Genocide. When I first listened to the tape, I hadn’t seen her for a number of years. Hearing her voice was a tremendously emotional experience — vibrations from my childhood awakened in my brain. At the end, she speaks directly to my mother, knowing full well they will never meet again. Her voice is kind, healing, optimistic — the voice of one who has worked and suffered and yet never complained. “Be happy,” she concludes. “It is all good.”

John Berbrich: That’s beautiful — & inspiring. That account epitomizes my impression of the generations — the old ones worked hard & didn’t complain; the young ones whine. I am aware that these are gross simplifications, but as I said, they are only my personal impressions. I presume that they have some basis in fact.

William Michaelian: Clearly. And examples abound. Dollface has worked in hospitals for many years. As a general rule, the older patients are the toughest, the most appreciative and understanding, and the least likely to complain, while many in their thirties seem to think the world owes them its undivided attention, and act as if pain is somehow beneath them. Ignorance, of course, is at the bottom of it. Many haven’t the slightest idea what real suffering is.

John Berbrich: I think that’s a large part of it. And too many people are confused about the difference between rights & privileges — & forget entirely about responsibility. Living well involves a sort of paradox: on the one hand, don’t ever forget that you are only a particle of cosmic dust; on the other, remember that in all the universe you are absolutely unique, a Monster-God of creation. Balance these two notions & you won’t fall over.

William Michaelian: Right. It’s necessary to embrace both. Fear one and you deny the other — you deny yourself. Here’s a poem I wrote last January:

Remember Me

All things testify according

to their natural, light-given truth:

leaves, twigs, meadows, and birds,

wild streams and errant tufts of fur,

dry weeds whispering remember me,

baked crust of aromatic earth.

I nod to the mossy water

conversing fortuitously in a ditch,

push back my hat, scratch my head,

wonder at the miracle of melted snow.

I rub dirty hands on threadbare jeans,

revel on bended knees to dig,

every inch a mile closer to myself,

past walls etched with veins of gold.

Summer speaks, autumn listens,

cold winter declares its grief.

When I care beyond my strength to know,

spring drags me out of bed,

makes rainbow tea,

butters my bread with sky.

I swallow the light and go outside.

In the wink of an eye,

my dreams no longer fit their shoes.

John Berbrich: I like the attunement to the natural world & also the speaker’s wonder at it. We get hat, shoes, & jeans as well as melting snow, birds, & sky. And I love that final line. Your poem reminds me of one that I wrote maybe 10 years ago — the transition from winter to summer.

In Cossack Spring

Forget that gentle motherly nurturing pap

Spring comes as a bold Avenger

Muscular, striding across the brown fields, the

gray fields, the white fields

Striding with green sword, broad & sharp

And the heaps of snow are pierced & dead

And the skinny icicles hiding in shadow

Shivering in clusters, are soon dispatched

Drip by drip, clear bloody drips

The pitiless rain, the pitiless sun

Beating, beating upon the frost

Drowning the ice, baking the ice

The fog upon the hill-tops staggers

The wind like horses, galloping, whinnying

The howling wind, the scream of Spring

And birds gloat in treetops, laughing

Trees sucking like vultures on Winter’s remains

William Michaelian: Ah, yes — a good, vigorous poem, visual and vocal. Isn’t it something, how we are influenced and shaped by geography? As witness we are moved, as participant reborn. Here’s another, written almost exactly a year ago:

Wolves

I sweep the floor,

but not beneath

your feet.

Your brow defends

the shadow

fallen there.

Frail sun leaves

ice unscathed

and windows cold.

Another winter

just begun,

bolder than the last.

Remembered warmth,

an empty glass,

pale worn out shoes.

The wolves are braver

this year, hungrier,

more brazen.

Inside, counting them,

I go mad as they

gather near the well.

What thick coats

they have, what eager

eyes and tongues.

What wild dreams,

framed by a rim

of naked trees.

I give a carefree

whistle, call them

to the door.

John Berbrich: Wow. I really like that one, Willie. The three-line stanza works as a perfect organizing technique. I love the insouciant way you call the wolves at the end. Has that one been published?

William Michaelian: Not in print. It’s another tiny piece of the puzzle that is Songs and Letters. But it’s yours if you like. If you have room in the Yawp and feel so inclined, I’d be honored.

John Berbrich: Great. Why don’t you e-mail it to me over the usual route. I can’t print off this forum thing. Clever design.

William Michaelian: That’s odd. I haven’t had that problem before. Did you try selecting the text? You should be able to copy the poem and paste it into your word program. But let me e-mail it. And thanks for giving “Wolves” a good home. So — as rugged as the seasons are in your area, I’ll bet you have other poems in that vein.

John Berbrich: Oh, yeah, I must have a few. I’ll look through my folders. But in the meantime — Thanksgiving is arriving soon. What does your family usually do? Host or visit? Or is it just like a normal day?

William Michaelian: Until a few years ago, Dollface, the kids, and I always gathered at my mother’s house. Now we have the main meal at our place, usually late in the afternoon. This year, our daughter has volunteered to serve as pie-maker. And, like last year, our son says one of his friends, a co-worker and former roommate, will be joining us. There’s a turkey in the refrigerator. The poor thing is cold, but he seems to understand. How about you guys?

John Berbrich: First there’s a big crowd at Nancy’s sister’s place. We gorge there & shoot pool, then cruise over to my mother’s — only a couple of miles away — to gorge &, well, relax. Relax & philosophize, solving all of the world’s major problems, virtually. It’s a grand day, Thanksgiving is.

William Michaelian: Sounds wonderful. When we lived in California and the relatives were around, our gatherings were much larger. We’re sort of isolated up here. My brothers are thousands of miles away and usually can visit only once a year. My father is no longer with us, and my mother’s health is failing. Together, they were two of the greatest hosts I’ve ever seen. Holidays aside, when I was a kid, people were always dropping by our place, and cousins were lined up at night sleeping on the floor. Good memories, great times. The good news is, all four of our kids are still in Salem. With any luck, in a few years our clan will have increased, and we’ll come full circle and the house will be full again. How old is your mother?

John Berbrich: Well, really she’s my step-mother, & I’m not sure about her age. Around 70. She’s in pretty good health. I’m the oldest of six kids & so is Nancy, so family gatherings have the potential to accumulate quite a throng. Now I’m getting hungry for a juicy thigh encased in crispy skin. Turkey, of course.

William Michaelian: Of course. But between here and there lie mountains of macaroni. And wide potato valleys. Sandwich trees and sugar-rimmed pools of cereal. You must be strong. You must eat your way to Thanksgiving.

John Berbrich: We started warming up tonight w/ a big salad & generous portions of all-wheat spaghetti smothered in Nancy’s homemade pesto. A singular culinary delight!

William Michaelian: We, too, like the heavy-duty spaghetti, with garlic bread to blot up the sauce. Lots of garlic. Lots of butter. When we’re done, my plate is so clean it doesn’t need to be washed. Tonight’s fare: bacon, eggs, and pancakes.

John Berbrich: What pigs these mortals be! This is real bacon, I’ll bet — not turkey bacon or soy bacon. Why is it that we are attracted to artery-clogging slozzle like this? I love it. You said it — lots of garlic & lots of butter. I used to lick my plate clean but now I leave it for the dogs. They are grateful animals.

William Michaelian: Real bacon, in all its salted, smoky glory. I’m a great believer in fruits and vegetables, but if a guy is going to keep in touch with his peasant caveman roots, he also needs his slozzle. Beside a campfire, it’s even better.

John Berbrich: Yes, we cannot afford to lose touch w/ the brute portion of our beings. Otherwise we’ll become androgynous consumers. Or disembodied floating brains, calculating the sale prices. Eat hearty, lad! Tomorrow’s the big day.

William Michaelian: That it is. Luckily, there’s still time for a hearty pile of scalloped potates and coleslaw. I think of it as mental preparation.

John Berbrich: Our preparation consists of roast beef, peas, & potatoes smothered in butter & gravy. I’m really getting in the mood now.

William Michaelian: An excellent low-calorie, low-cholesterol meal. Peas are such cheerful little beings. Have you noticed? They always seem so happy, dimpled and steaming in a bowl.

John Berbrich: Yes, the simple, lowly pea. Today’s quote has to be from T.S. Eliot — “We are the stuffed men.”

William Michaelian: How appropriate. And we are leaning together, headpeas filled with straw. Alas!

John Berbrich: I don’t think I’ve ever experienced headpeas, Willie. Why don’t you tell me about them?

William Michaelian: There’s not much to tell, really. Headpeas are the peas in charge of the other peas.

John Berbrich: Ah, you mean the pea-brains. I have heard of them. Quite a lot of trouble they cause, too.

William Michaelian: Right. More often than not, they can’t be appeased.

John Berbrich: Although they can be threatened by a peashooter.

William Michaelian: I knew a peashooter once. He had corns.

John Berbrich: And his corns had ears.

William Michaelian: Which he served with bunions.

John Berbrich: As the potatoes eyed him.

William Michaelian: And sang I yam what I yam.

John Berbrich: Deep in your artichoke heart, Willie, you’re a beet poet.

William Michaelian: I’m a poet and don’t know it. But my feet show it — they’re long fellows.

John Berbrich: Lettuce move on from these terrible puns.

William Michaelian: Gladly. Besides, there’s no way I can top your brilliant artichoke and beet poet puns. So — I bought a used book the other day: a biography by Jean Francois Lyotard called Signed, Malraux. Just got started. Written in an energetic manner. Lyotard — that name is one reason I got the book — doesn’t mind asking questions and stating his opinion. I have Malraux’s Anti-memoirs. I read a few pages two or three years ago, then put it down and never went back to

it.

John Berbrich: Wasn’t Malraux a biographer — or am I thinking of someone else?

William Michaelian: Must be someone else. André Malraux was a novelist — Man’s Fate won the Goncourt Prize and is his most famous work. Over the years, he was mixed up in all sorts of travels, adventures, and politics. Born in 1901, he spent time in Cambodia during the 1920s searching for the Khmer temples, then edited a political paper in Saigon, and also spent time in China. He fought in the Spanish Civil War and served in a French tank unit during the World War II. He was even Minister of State for Cultural Affairs for about ten years. He visited the U.S. in 1962 and arranged for the Mona Lisa to be shown in this country. Anti-memoirs was written later in his life. It’s billed as autobiography, but he uses excerpts from his novels and a mixture of fact and fiction. Malraux died in 1976.

John Berbrich: Well that should be an interesting biography. You wonder how these guys found time to write, these fellows who traveled all over the world & fought in wars & so on — writing novels would seem to be a full-time job. Must be they didn’t waste any time.

William Michaelian: They were restless, driven. Frustrated. Angry. Disturbed. Possessed.

John Berbrich: We, on the other hand, are lethargic, torpid, phlegmatic, languid, sluggish, dull. No wonder I never get anything done.

William Michaelian: Folks, I’d like you to meet John Berbrich, author of the new novel, Inertia.

John Berbrich: Oh, & I’m a procrastinator too.

William Michaelian: Is that why you get up at five in the morning? So you have time to put things off?

John Berbrich: You got me there. It ain’t easy getting up at that time every day. But you’re an early riser, too, I understand.

William Michaelian: I am. Seven days a week, year in and year out, without an alarm, no matter how late I hit the sack. These days, that’s usually close to midnight. My mother has Alzheimer’s Disease. I’ve been staying with her for the last six months, spending nights at her house, and most of my days as well. She tends to sleep until about nine, so by getting up early I’m still able to get some work done. It’s a tough situation, because I wake up several times during the night to see how she’s sleeping. Under the circumstances, I suppose I should learn to sleep in like a normal person, but I can’t bear the thought. I’d rather be tired. Work is my salvation — has been for many years. At the moment, though, I’m at home, listening to our youngest son play Gordon Lightfoot’s “Affair on 8th Avenue” on his guitar. By the time you read this, I’ll be at my mother’s again. Life is something, isn’t it?

John Berbrich: It sure is. A surprise around every corner. It’s good to make plans yet it’s also good to be flexible. I had no idea you were tending to your mother like that. I’m no workaholic, but I feel so useless if I’m not working on several projects simultaneously. Combined w/ my lethargy & tendencies toward procrastination, I’m usually in a muddle. You, Willie, are a good son.

William Michaelian: I don’t know. It’s a strange journey we’re on — sad, but beautiful at the same time. The situation has certainly had an effect on what I write.

John Berbrich: What do you notice that’s different? A new perspective — or maybe a deepening of old notions.

William Michaelian: The latter, I think. But maybe that amounts to the same thing. Out of necessity, my focus has been on shorter pieces, both poetry and prose, some of which are quieter and darker, but without being bleak. I definitely haven’t lost my sense of humor. Songs and Letters, now in its tenth volume, is my main focus. From the outset, I wanted the book to reflect whatever life threw my way. So naturally my mother’s illness and my being here with her has become part of it. In a way, I’d even say she is helping me write the book, while also hindering its progress.

John Berbrich: That makes sense. Regarding Songs and Letters (great name, by the way), what do you mean by tenth volume? The word volume suggests to me an actual book on paper.

William Michaelian: Good. Because while the book presently exists only in electronic form, it is a book, and my belief and intention is that it will in fact eventually see print. The volumes are sections that each have their own character, differentiated by subject matter, treatment, form, or a combination thereof. The end of each serves as a natural pause or jumping-off point in the text. The volumes are such that they can also be published separately. At the same time, partly because of the random nature of the Internet, and partly because I envision the printed version as something of a bedside reader, I am writing the entries in such a way that they do not have to be read consecutively. Each stands alone. But each is also meant to arouse curiosity as to what might have come before it and what will follow. To complicate it further, the pieces are totally spontaneous and unplanned. Uncharted is one word I use to describe them.

John Berbrich: Sounds fascinating. Really. How many pages do you think the ten volumes would comprise, in book form?

William Michaelian: Good question. At the moment, there are 358 entries, many of which would use only one page. A few are longer — say from 700 to 1,000 words. The tenth volume is still in progress. So at present, just as a rough guess, I’d say between 400 and 450 pages. Because even the shortest of poems, I think, should have their own page. Like this one, for instance:

Epitaph

what strange liquor is this?

who poured it into my glass?

why do I love its flavor?

why can I not resist?

John Berbrich: Wow. There’s a lot in that one. Each line expands the scope of the poem as you read down. It grows & grows. Although the title helps to narrow it down. And what’s funny is that although each line asks a question, each question implies many more questions. It is the other questions that seem to make the poem grow. Beautiful. Excellent. Ruminative.

William Michaelian: Thank you. I appreciate that. Each time I add an entry, it’s like setting it free and hoping it takes flight. Sometimes, it’s like I’m already in flight. Anyway. This is what I’m up to these days. One thing that makes the project interesting is that I have no idea when it will be done.

John Berbrich: An open-ended project. When it’s done, you’ll know it. Frank Zappa once said that he knew a song was finished when he was sick of working on it.

William Michaelian: Zappa, and several others. Well — on that note, we seem to be at a good stopping point, and this page is long enough to daze even the most charitable of readers, so let’s say farewell to Rasputin and start a new one.

Main Page

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation

Join Conversation